I don’t remember actually sleeping that evening. We laid there from 6:00 PM until about 8:30 PM, and I tried to settle my thoughts, to achieve some sort of mental—if not physical—rest. But, my monkey mind continued chatter and squawk. I must have drifted off briefly, though, because when I checked my watch for the last time I was surprised that night had fallen.

In spite of the prep I had done before closing my eyes, there was still business to attend to. I forced myself to eat a snickers bar (prewarmed in my sleeping bag) and some smoked almonds. I drank water from my HydroFlask, but it did not feel good going down, and I ended up consuming less than I had planned. The strategy had been to gorge myself on water before leaving, maybe swallowing 750 ml, then carry 1,500 ml up the mountain. This “pre-hydration” has helped me in the past, but that night it was tough to get even 500 ml down that night at Camp 4.

Getting the electronics set up, and ensuring that I had forgotten nothing, were the top priorities. I was too busy to even send a message to Julie. And, like the previous night, I resolved to evacuate my bowels before leaving. I really had no biological calling for this, but the thought of getting the urge on summit day was unacceptable. Preparing for that experience was a hassle, because this time I did it wearing O’s, which meant stuffing the bottle into my pack and dragging it out of the tent with me.

Crawling from the vestibule into the night was a shock. It was COLD outside, even though the wind was relatively light. Scattered flakes of snow blew across the Col, falling at a 60 degree angle, streaking by in the orb of my headlamp and illuminated in freeze-frame by the rhythmic flash of two strobe lights duct taped to the radio antenna on IMG’s main tent. I had worried for years about the calamity of descending in a whiteout and failing to find my way back to Camp 4, which is what happened to tragic effect in 1996. This should never happen in the modern era, both because lines are fixed almost to our doorstep up there, and also because of GPS technology. In fact, I carried two GPS units that day: a Garmin Fenix2 and a Delorme InReach. Plus, I would never climb alone. Even so, the strobes seemed like a stroke of genius as a last ditch backup.

Sherpa guides and team members were busy, moving with purpose in the black night. Energy… chaos… flashes of white headlamps… a hundred tasks being performed at once… faces obscured by darkness and oxygen masks… all in the snow and wind. Welcome to the show. This is it.

In the distance, snaking up the Triangular Face: a line of headlamps stretched up the mountain. My heart sank. Holy shit, why are so many people up there so early? Maybe it would be better with them ahead and out of the way. That’s what I told myself. But, in truth, this was exactly what I did not want to see: The potential for a major traffic jam on the route. Get moving.

I walked for a minute towards Tibet, to a quieter area of the Col, and took care of business. Highest latrine on Earth. In the end, it turned out that I had almost nothing in my system, and I should have just skipped this. It was a waste of time. At least I had one fewer thing to worry about.

When I got back to the tent, Steven and Kim were just about ready to leave with their Sherpa guides. Although I could not identify them, I knew that Cristiano, Emily, and Siva were also gearing up nearby. Justin and two of our teammates, Nicky and Bob, had left an hour earlier. Come on Paul! Move it! On went the harness, on went the spikes. Why won’t my left crampon sit properly? I just could not get it to seat snugly… it was almost perfect, but not quite. Well fuck, of all the times for this to happen… Goddam Vasaks. It was so tempting to just cinch the straps down and start walking. No. Make it right. This is Everest. No shortcuts. Finally I got them on, solidly and perfectly, tightened them like never before, and stashed the strap tails in my boot gaiters. The effort left me almost breathless.

When I stood up, Kim insisted that we pause for a photo. She and Steven had their packs on, and were already masked up.

Water! I had not yet resupplied. The Sherpa climbers had been working hard, all day no doubt, to melt snow into drinking water for everyone. This was the big rush hour, and it was tough for them to fill all the orders at once. I told Kim and Steven that I needed another 10 minutes to get my water and get my pack on. They were ready to go and it was cold. Clearly, they needed to leave ahead of me. And so they did.

Moments later I realized that there was another team heading out, a group that was camping to our left. I did not know them, but they seemed numerous, perhaps 15 climbers. This added a sense of urgency to our departure, because I did not want to be separated from my friends by a posse of strangers.

I primed the MegaWarmers in the flow of oxygen in my mask, and massaged them to maximize their contact with the atmosphere. Come on babies, catch on. It’s really impossible to tell whether the warmers are working right away when it is so cold outside… they need to simmer inside gloves to have any effect. I stuffed them in on a leap of faith. They had worked well for me on Aconcagua and Vinson… not at all on Denali… and I had never used them at 8,000 meters before. I had sustained minor frostbite to my fingertips while pitching high camp on Denali in 2012, when the wind blasted down from Denali Pass at the very moment we arrived at 17,300 feet, and it had taken a couple of hours to dig in and build camp from scratch. Ever since then my fingertips have been more susceptible to the cold. Today would be their ultimate test. I climbed in Smartwool glove liners and OR PointNChute’s, the single-wall leather lobster gloves that had served me well so far on Everest 2015 and on Vinson. I also carried OR AltiGloves and MH Summit Mitts as backups, but both of them came at the cost of reduced dexterity. And, although the AltiGloves had nice palms, I was not convinced that they contained enough loft in their backs to justify using them. Months later, when looking at photos from the 1963 US expedition, I was amazed to see beaver skin sewn to the backs of their mitts… the only piece of gear they used that made me jealous. If I were ever to got to 8000 meters again, I would sew fur to the backs of my gloves. For that night, I hoped that my two lighter-weight gloves would do the trick, so long as the chemical warmers did their part. Catch on, just one more time….

Minutes later Pasang Kami brought my water bottles back, full. As at Camp 3, they contained warm—not hot—water. And, as before, I knew that my HydroFlask would be fine, but that the 500ml Nalgene bottle would freeze sooner, even if I kept it insulated in an extra thick wool sock and carried it in my down suit’s inner chest pocket. No worries, just drink the Nalgene first. I made sure the lid was sealed tightly, then slipped a sock around it and put it into the suit pocket upside down. This way, if ice formed earlier than expected, it would float to the inverted bottom and not clog the opening (a trick I had learned the hard way climbing Mt Rainier for the first time in 2008).

Pasang Kami was ready to go. In fact, he was eager to get moving. Something was askew with Siva’s climbing Sherpa, whom we could not locate. I suspected he was off taking one last leak, and that he would be back soon enough. We needed to leave. So, I shouldered the pack: Feels lighter than yesterday. You can do this. I turned on the InReach tracker, dialed my HotTronic boot warmers to low setting, and Pasang Kami and I started walking. I assumed that Siva and Emily would catch up in a few minutes. I triggered the GPS tracking feature of my watch, and started the timer. It was 9:25 PM.

The trail from Camp 4 begins flat. In fact, it drops a few feet into a shallow depression before starting up the ice face. This gentle start was a blessing, because it allowed me to increase my breathing rate and tweak my systems a bit—adjust the balaclava, get the hip belt just right, make sure the mask was not leaking, etc. Paying attention to these details helped distract me from the big picture. Take one step at a time. Just like any other mountain.

A minute after we started, Emily called Pasang Kami on the radio, urging him to send Siva’s Sherpa back for him. We could not understand what she was talking about. I realized that there was indeed another Sherpa climbing with us, someone who I did not recognize…. But, we confirmed that this was not the person Siva was looking for. I called her back on the radio. “I’m so sorry Emily, there must be a miscommunication… but he’s not here. We are moving out.” I was working so hard—even on the flat terrain just beyond camp—that I did not think to ask who this new person was. He was clearly a friend of Pasang Kami, and that was all that mattered to me.

It was not until I reached EBC days later that I realized this had been my second climbing Sherpa, hired specifically to haul my extra oxygen bottle to the South Summit. IMG’s bottles are substantially bigger than the Poisk bottles carried by everyone else, but not big enough to last the day, especially at the high flow rate I had chosen: 4 liters per minute. I wanted this flow rate to keep me warmer and to provide a greater safety margin. I love my brain, and use it almost every day… the thought of coming home with hypoxic neurological injury was just too scary for me.

By breathing 4 LPM, I would need a fresh bottle at the Balcony like everyone else, but also another one at the South Summit. My teammates who were breathing 3 LPM could make do with two bottles for the whole day, changing into a fresh one at the Balcony, then getting back into that bottle on the way down if necessary. Regardless, all of these extra bottles needed to be carried by someone… and as usual, our climbing Sherpa partners did the heavy lifting (about 20 lbs of extra weight, in addition to their own bottle, which they used at a lower flow rate than we did). I had never bothered to ask who would carry my third bottle… I figured it would be one of our Sherpa fixing lines at the start of the season, who would leave it there, waiting for me. But, of course, that would be an unreliable plan, for a variety of reasons. Instead, a Sherpa climber had been hired expressly for this purpose to climb with me the same day. His name was Ishi. Not only did he turn out to be a super strong climber, but also he was kind and patient. Without him I would have had a much tougher day. He was worth every bit of the extra $6,000 I had paid for that fourth liter per minute of oxygen.

But, again, I had no idea who he was when we were leaving Camp 4, or why he was with us. My focus was on keeping up with Pasang Kami.

The route rises gently from the shallow depression immediately below Camp 4. On any other route, on any other mountain, this initial climb would be a small hill, a mere bump. That night, as we started out, it felt like a big deal. Pasang Kami was moving very quickly, almost as fast as I walk at sea level (and back home no one passes me on foot). Here, at 26,000 feet, his pace was too fast for me, at least from a cold start. I felt as though I were almost jogging behind him. This would not be sustainable! But, sure enough, he had good reason to hightail it from the get-go: there were plenty of headlamps behind us. He wanted to position us as far forward in the column as possible, before it consolidated and locked us in behind slower climbers. His instincts were right… but was an exhausting way to start the day.

Unusually deep snow blanketed the South Col and the Triangular Face. Most years, this area is a mess of loose talus which requires care underfoot. For us, the walking was easy: All we had to do was follow the fixed line and put one foot in front of the other into the soft steps kicked by our predecessors. I do not recall my crampon points scraping rock more than a few times all day.

After about ten minutes the route eased off briefly, on a kind of high bench of snow, below the proper Triangular Face. This allowed me to catch my breath while matching Pasang Kami’s pace. There was a sense of urgency because I wanted to put plenty of distance between us and the column of strangers on our six, and because I wanted to catch up with my friends on the route ahead. I recall thinking that someone was right behind us… of course, this was Ishi, our friend, but in my addled state I got confused and thought him to be a stranger.

I looked up at the line of headlamps winding its way up the mountain. The climbers ahead seemed to be at a standstill. There’s no rush to catch up with these assholes. Climb slow and steady.

To our left, well off the route, I saw two red headlamps. Just sitting there, quietly, not moving. No matter how hard I tried, I could not make out the climbers wearing them, or understand what they were doing over there. I figured they were people taking photos of the route, perhaps a time exposure shot. To this day I do not know who they were or what was going on over there. I suppose these could have been climbers lost on their way down (or up), but the route is so clearly marked that it’s hard to imagine this happening, and they would have no reason to use their tactical lights in that situation.

The snowfall tapered off, and the wind remained light. I had no trouble keeping my eyes moist without wearing my goggles. I figured the wind would kick up at any moment, and kept the photochromatic Zee-goggles at the ready in my inner chest pocket. But, the wind stayed gentle enough that I could climb without wearing them, which simplified things.

As we moved higher I realized that the clouds had parted. I never dared to hope that we would see the full moon, but now it bathed us in pure white light. You are climbing Everest under a full moon on a clear night. This is happening.

After a short time the route became steeper again, a sign that meant we were on the Triangular Face proper. OK, you can do this. I looked up the route and saw a long gentle line of headlamps arching upwards.

I craved information about my teammates. Pasang Kami, Ishi, and I were separated from our friends. I hated that feeling. Where is Kim? At one point on the radio I heard a climber on the Classic team turn around. I was so sorry for her, and wanted to give her encouragement when we passed each other. I watched for her for the next hour, but never crossed her… which only made sense later, when I learned that she had started shortly after I had.

My plan was to cycle endlessly through the systems, from head to toe: How is my headlamp brightness and beam angle? Are my eyes protected properly? Are my cheeks still covered by the custom balaclava fabric flaps? Is the oxygen still flowing well, or do I have rime building on the outflow port… think of Phil Ershler and poke the blowhole with your thumb just to be sure. Am I using pressure breaths to ensure auto-PEEP? Am I too hot or cold? Should I adjust my suit zipper, or the base layer zippers? How are the shoulder straps? How are my hands… should I change into heavier gloves? Is the backpack hip belt proper, or too loose? The harness: Is it still cinched fully tight? Any slippage of the knots in my safety or ascender? Is ice building up in the ascender’s jaws? Remember to flick the trigger at the next anchor just to clear any ice from the track. Do I need to pee? Are my genitals lined up properly and warm enough? How are my legs… should I adjust the thigh zippers? How are my boots… are the liner tongues still midline, or are they migrating laterally, in spite of Dave Page’s custom velcro retrofit? Are my feet warm enough… or too warm? Should I turn the HotTronics up or down? Are the crampons feeling solid? Are the strap ends still tucked into my gaiters? Are snow balls building on my soles? What time is it, and how is my pace? Do I need to eat or drink now? Have I still got a PowerBlast gummy in my mouth, or should it be replaced? If I went through this checklist over and over again, the risk of missing a failing system would be reduced, and I could take care of any issues before they threatened my summit bid.

At least, that was the plan.

In reality, I became consumed by the stress and strain of climbing—especially dealing with traffic on the route. Rather than focusing on myself, I focused on everyone else up there. Climbers in front of us packed the line. They were so slow that I could not quite believe what was happening. True, I was climbing on 4 liters per minute, which is like putting nitro into a supercharged muscle car and asking it to putt along behind a bunch of Yugos. It was up to me to pass the people ahead. But… they really did not want to be passed, and they made it difficult. I could not understand why. If I’m driving along the highway and someone roars up behind me, flashing their lights and blowing their horn, I always let them pass… especially if I am driving 35 MPH in the fast lane. Why didn’t these guys do the same? All they needed to do was take another breath or two, long enough to allow me to clip past them, one by one. And that’s exactly what Pasang Kami and I did when they ran out of steam and folded at the waist, sucking wind. But, often, they made it tough for me to get by. In a few cases I grabbed their ascenders to prevent them from advancing while I stepped past. “Namaste!” I shouted in a universal greeting, even though they were not Nepalese. They looked back, blankly, from behind goggles and masks, anonymous, silent, like sleepy cattle, or stones in a stream. I thought, Namaste you motherfuckers. GET OUT OF THE GODDAMN WAY!

Of course, I could have unclipped any time and climbed past them. Pasang Kami was happy to do that, I could tell. But, I had promised myself that I would never unclip. No more Cristianos. So, we worked our way up the column bit by bit, in a frustrating process.

At some point the calendar changed from May 20 to May 21. Looking back at the GPS track now, I can see that midnight arrived when we were about 90 minutes below the Balcony. But, I did not keep track of the time. In fact, I never looked at my watch on the Triangular Face. Not once. I was unaware of the true passage of time, but felt the agony of every moment wasted on the route while standing still. I counted my breaths: After three breaths I was ready to take the next step comfortably. On one occasion I counted 100 breaths before the line moved. Every minute felt like an hour, and hours passed like days unto themselves. My shot at the summit was slipping away, outrageously, because of the traffic jam.

At one point, when their leader sat down on the lines above us and turned back, I hooted and hollered from 50 meters behind, tried to signal to him by making the SOS signal with my headlamp, and danced a macarena of rage, signaling him to step aside or get moving. There was no reply. He simply stared back. I memorized his suit, and vowed to chew him out when I passed him. Instead, when I finally did reach him, I realized that he was just another stunned, hypoxic person stumbling up the mountain like his teammates, staggering into an environment where he did not belong. He had not meant to be rude. He was simply pathetic. I almost pitied him. Almost….

Once we extricated ourselves from the knot of strangers, there was nothing else to do but put one foot in front of the other, take 3-5 breaths, and repeat. Even bathed in full moonlight, the mountain felt dark, steep, and forbidding. Black rock bands hovered in the snow like shadows, and became milestones for me to mark and aim for, one by one.

It was bitterly cold but I did not feel it once we passed the traffic, when movement kept me warm. My hands were always on the verge of feeling cold, but never quite in trouble. Same with my right great toe, for some reason. I would have thought that its size would keep it warmer than the others, but it did not work out that way. I never felt the need to turn up the boot warmers, but it was good to know I had the option if necessary. Hours later, on the descent, I would discover that the right battery would only trigger for a few seconds before cutting out… perhaps it had accidentally discharged in my pack in the previous days, and was never on during summit day.

The route took us through a narrow trough of rock, like a tight corridor, barely wider than my shoulders. There was just enough snow below to provide purchase for the crampons. Thinking back on it, that section would have been aggravating on a normal year when the slabs are bare underfoot. But I liked being able to grab the wall with my left hand while advancing the ascender with my right. This is the spine of the mountain. You are touching Everest.

I saw a light twinkling above, on a ridge atop a particularly steep snowfield. A headlamp, shining down upon us. I aimed for it.

Tough going, that last pitch. When we finally got within hollering range of the light, I saw many other climbers sitting or standing still on a small flat area, maybe 20 x 30 feet. This must be the balcony.

The headlamp called out to me in a voice muffled by an oxygen mask. “How ya doing, Paul?” It was my guide, Justin! I have rarely been so relieved to see a friendly face. Justin had left an hour ahead of me, and I feared I would not see him again all day.

“Justin! Lots of traffic. Sorry I’m late.”

“You’re fine. Come on up, get your pack off, and get some water and something to eat.” He could have been coaching me on any other day. It was soothing to hear this. I found an empty spot in the snow and gladly dumped my pack. Nicky was there, and she greeted me warmly. I realized that something was not right with Bob, perhaps diarrhea, but I was too tired to investigate. Steven was there too, taking a break. I checked my watch for the first time all night: I had been climbing for 4 hours, 13 minutes. The goal was 4 hours to the Balcony… so, in spite of the traffic, I was doing fine.

Interesting how often the mountains are different from what I expect, no matter how much homework I do. I have read of the Balcony for years… somehow, I envisioned it as a small cliff jutting sharply from the mountainside… like a balcony! In fact, there is no balcony at all. Instead, this is a small flat area which is totally exposed on all sides. It is the meeting place of the Triangular Face and the Southeast Ridge. Rather than a sheltered cove, it was exposed to the whole world. For the first time I saw the wild and wooly Kangshung Face dropping away to the east, concealed in the dark sky, just a few hummocks of snow glowing in the moonlight. The Kangshung is one of the most austere faces on Planet Earth, and a deadly serious place. Just knowing what I was looking at left me feeling creepy and wary. I looked for the sunrise over Tibet… but no dice. It was only 1:45 AM.

I didn’t have to ask about Kim and Cristiano. It was hyper-cold at the balcony, and there was no way anyone could stand still there for long. I knew they had proceeded up the route ahead of me.

My plan was to pee, eat, drink, and rest.

I had no urine to pass.

I had no appetite, but forced down some cola-flavored Power Blasts.

I was not thirsty, but swallowed some cold water from the small Nalgene, perhaps 250 ml.

I began to shiver. I looked up at the route ahead: just a few headlamps above, snaking steeply up the ridge. It felt more like our mountain now, with these familiar faces around me. We can do it.

While I had been sitting during the break, Pasang Kami had kindly swapped out my oxygen cylinder. Justin looked even colder than I was—no doubt because he had been standing around for over 30 minutes waiting for me to arrive. It was time to go.

I stood up and shouldered my pack, which suddenly felt profoundly heavy. Oh my god. I shrugged my shoulders and struggled to fasten the hip belt, but just could not get it to click securely into place. The down suit obscures the belt, as does the O2 mask… and my thick gloves reduced my ability to feel anything fine or subtle. I tried several times but could not get the belt to fasten. And I began to feel that I was dying. Time slowed down, and I could feel my pulse in my ears, ringing loudly. I fought a sense of panic and doom. I can’t stand up… how can I climb if I can’t stand? If I can just get moving and get my heart rate up again, I’ll compensate. Unless I die trying.

“What’s wrong?” asked Justin.

“I’m OK,” I lied. “My belt. I can’t see it. Can you help me?”

“Well that doesn’t sound right.” He stepped towards me in a familiar way: calm, relaxed, and wise. As if he were back in the regular world of low altitude, a different world from me. Didn’t he feel like he was dying, too?

“When something’s wrong we always start with oxygen,” he explained. “What’s your flow rate?”

“Four,” I shouted desperately.

“Let’s see.” He opened my pack and examined the valve and gage. “Yep, dialed to 4 liters, but the valve is closed! You’re getting no oxygen.” I felt him turn the valve, and became aware again of the hiss of gas flowing into the reservoir. I breathed deeply. And I began to come back from the odd place I had been.

“Thank you. Thank you. Better.”

“When something goes wrong, always start with oxygen, and make sure it’s on!” I think he was talking to Pasang Kami as much as to me… but this was on me, and no one else. It had been kind of PK to change my bottle, but ultimately it was my job to look after myself. No epics up here….

We began to climb away from the Balcony: Lakpa Nuru, Steven, Justin, Pasang Kami, and me. I assumed that Bob and Nicky would follow soon afterwards. Emily, Siva, and his Sherpa guide had not yet arrived.

The Southeast Ridge was the most mysterious portion of the climb for me. It is rarely photographed or written about. This is because it is climbed at night, when photos do it little justice, and everyone is too tired to snap it anyhow. And, on the way down, most folks do not want to pause to photograph it—they want to get the hell out of the death zone.

So, for me, this felt like climbing into an unknown realm. And it was amazing. Those first sections after the Balcony rose gently into the night, in beautiful arcs that undeniably resembled the backs of whales breaching the surface. The snow squealed underfoot in a sound like styrofoam being crushed. The lines were clear. The moon was full. We were climbing as a team. It could have been Mont Blanc or Rainier, except we were at 8,400 meters. It was spectacular.

The route grew steeper and steeper, almost imperceptibly, until at some point I realized that we were on 50-60 degree terrain. I never felt exposed, perhaps because I was surrounded by friends, and because I could not see much beyond the orb of my headlamp. Besides, there was no time for fear, no need to indulge in it. Hours later, during the descent, the full magnitude of our exposure would be revealed, with drops of thousands upon thousands of feet in all directions. A mistake here would kill us, period. But the job on the ascent was simple: Take that next step, slide the ascender up, take three breaths, then repeat. The only direction was up.

Periodically, dark rocks would emerge from the snow, providing handholds. Even through my thick gloves the mountain felt cold. People do not belong here. I found new meaning in King Crimson’s lyrics: This is a dangerous place.

And then, we hit traffic again.

I looked at Justin and gestured to the climbers above us, as if to say, “You see what I’ve been dealing with all night? Please fix this!”

He tried, lordy he tried, negotiating politely with the others when possible. But there is only so much that can be done in tight quarters with so much exposure on all sides. There’s no way any of us was going to unclip. And so we passed them one by one when the opportunity arose. I drew strength from climbing with Steven, and did not want to get separated from him. Long pauses began to feel interminable, and that right great toe got cold. As we passed the teams above us, I wondered whether we were still on schedule, whether we would make it to the summit in time.

The wind blowing in from the West was cold, and it strengthened as we went higher. Even with my custom balaclava on, a bit of skin was exposed around my eyes, and it felt the breeze. Getting the goggles on would require effort, a small pause… we had plenty of those. And yet, so long as my hood was up, my face felt fine… although it kept catching the air and blowing back off my head. Even the effort of wrapping the goggle strap around my hood seemed too much… I just held the hood in place with my left hand when the gusts came.

The dawn arrived so slowly that I was barely aware of it. I had looked to the horizon over Tibet time and again. Come on, sun. Come on. Warm me up.

And then, suddenly, I realized I was looking at the sunrise. Clouds thousands of feet below formed a soft carpet, obscuring the earth from view. It looked so uncannily like Rainier had on the upper Emmons Glacier, except this was much steeper…. and twice as high.

I wondered whether our shadow was showing, and looked over my left shoulder. And there it was.

Below us, the string of climbers we had just passed labored on the Southeast Ridge.

Above us, just a few meters higher, the mountain topped out in the false South Summit.

I need to photograph this. It will slow me down. It’s worth it.

Justin had positioned us in a way to pass the final knot of traffic ahead when I realized that I was suffocating. Indeed, I believed I was dying. I tried to clear the valves by breathing on them hard, as we were trained to do, but I could not. “Justin.” I called out. He was several climbers ahead of me, in fact had just passed someone, and could not hear me. The timing was terrible. If I can just catch up to him, Justin will help me. Why can’t I clear this mask? I recall feeling my body shutting down exactly at the moment when I tried to increase my pace to catch up to my teammates.

“Justin!” I called out again. He must have heard me over the wind, because he turned his head slightly. “JUSTIN! MASK!” I fell to my knees, and slid the ascender forward until the tether was tight, and prepared to pass out.

But I did not pass out. I watched him descend a few steps to me, swiftly and carefully. “What’s wrong? Oh, I see. You iced up! You know how to fix this, silly!”

“I tried! Sorry.” I was gasping. I felt pathetic. He removed his mask, leaned in closely, and gave a few long, hot exhalations onto my intake valve. The ice plug broke free and I instantly felt the obstruction pass. I sucked in the deepest breath of my life—I could breathe again! “Thank you! I’m sorry. Thank you. That’s the second time you saved me today.”

“All you had to do is crack the seal on the mask.” He was correct: with intake issues, you can always bypass the obstruction by breathing ambient air around the valve. I knew that. But, my brain was not working right.

“Thank you, Justin. I’m good now.”

“OK. Let’s go.”

The South Summit is simply a small snow prominence in the sky, marked by a few aluminum pickets thrust into the ground and some O2 bottles clipped to the fixed line. On the left, jutting out over Tibet, a huge cornice caught the rays of sunrise. Beyond that, our first view of the summit block.

I had imagined this moment, hourly, for the last few years. I knew what this would look like. And yet, it was different. In my mind, the summit ridge curved westward, to the left. In reality, the route was pretty much in a straight line with the Southeast Ridge. I saw the Cornice Traverse, the Hillary Step, and the snow benches beyond. A cloud plume jetted away into space, blown by wind from the West. I had seen this before—thousands of time in my mind—and yet, now it was so… vivid. So real. This was real. I was doing this. We were doing this.

We were about to summit Everest.

But, first, we needed to drop down from the South Summit into a small col. Justin led the way. A rocky outcrop, approximately the size of a small house, reminiscent of Washburn’s Thumb on Denali, stood in our way. The route descended to the right, on a small snow shelf about a foot wide, hugging this rock. On the right, a vertical drop to the clouds beneath. I could not see the bottom, but knew that Tibet was there, about 10,000 feet below. I watched my foot placement very carefully. Giddy up….

The small notch below the South Summit is relatively protected from the wind. Justin took off his pack for a break.

I sat on the cornice, numb or oblivious to the objective hazard. Justin and Pasang Kami stopped on the scree slope, where a few Poisk bottles littered the ground. I knew Rob Hall was there, a few meters down the slope, and I intentionally chose not to look for him. Water, but no calories went in. “We’ll be there in 20 minutes, right?”

Justin laughed slightly. “An hour if we haul ass. It’s still a ways. Take a good break.”

“My god you are kidding me. It’s right there….” But he did not have to tell me twice to rest. I was baked.

I was amazed to see my third O2 bottle sitting there, with my initials I had written with a sharpie days before, clipped to an anchor. Exactly as promised. And I thought, IMG is amazing.

Pasang Kami offered to change out my bottle, and I thanked him. Instead of prepping the new bottle first, he instead turned off my current bottle then began to fiddle with the new one, trying to fit in into my pack, before hooking it up and turning it on. My 70 liter South Col pack was a tight fit. In frustration he began to jam and slam the bottle in there, crushing whatever might be below it. I thought of my med kit, my pills, my GoPro, all of which might be pulverized. Without the supplemental oxygen I felt weak and impotent, even sitting on my ass. “Justin!” I called out.

He looked over, and I gestured to the situation. “O’s. I need O’s.”

“Pasang Kami what are you doing?” Justin said amicably. He stepped over and got the gas flowing again. And again, I felt myself reborn. I thanked both of them for what they had done, and took the pack back and arranged its contents.

The plan had always been to shoot the entire summit ridge in HD video. I had battery and card space for that. But, now that I pulled the camera from my pack and inserted the battery that I had kept warm in my inner chest pocket, and hooked it up to my custom USB charging cable, I was unable to get the GoPro to turn on. Fuck. Really? What kind of action camera is this? All this time and prep…. fuck. It simply would not turn on due to the cold. It’s OK, I rationalized, I will shoot the descent.

As we prepared to move away from the break, I saw a small group of climbers walking towards us, on their way down from the summit. I recognized that little yellow and black suit… It was Kim! My friend. My teammate. We had been through a lot together. This had been a long time coming. She hugged me and grabbed me by the shoulder. “ALMOST THERE!” I smiled big enough that the seal broke on my mask.

She looked strong and confident. I was profoundly happy for her. “Congrats, Atomic Girl. Rock on, see you down there.”

Other members of IMG Team Hybrid passed one by one, and we congratulated and encouraged each other. Mingma… Cristiano… then Nima Dorje. In a moment, they were gone.

The Cornice Traverse begins just after the South Summit notch. This section is not particularly steep, but it links the South Summit to the Hillary Step. The route was hypercomplex, with multiple anchors in the cornice itself and lines in various states of decay attached to them. I was looking for our familiar “red rope,” the line I knew was fresh for that season, but I do not recall seeing it beyond the South Summit. Instead, a mishmash of black, grey, and other colored lines were cobbled together. Don’t haul down too hard on these. At one point, the route split into a “high” and “low” option, with one side about 6 feet above the other. I hesitated for a moment, then chose the high road. You’re Scottish. Take the High Road. I leaned with confidence against the cornice, a bulwark of compact snow ice that separated me from the Kangshung Face and Tibet below.

Immediately after the Cornice Traverse the route pitches up steeply to the fabled Hillary Step. Just before this, there is a relatively flat spot, about the size of a small room, wide enough for two climbers to pass one another without much difficulty. On climber’s right, this spot is relatively sheltered by the cornice and its granite base. On the left, the mountain drops away gradually at first, then steeper and steeper until falling into oblivion.

As I approached this niche, a group of perhaps four climbers approached from the Step, on their way down after the summit. They looked relaxed and in good shape. Except for the leader, who was terrified, with blue eyes wide open, gesturing hurriedly towards the mask. I immediately identified the problem: A huge white icicle sprouted from the mask’s intake valve. This was exactly what had happened to me about an hour earlier. As we walked a few steps closer towards one another, I realized that this was not a man, but a beautiful woman. An American flag patch was sewn to her red suit. “Are you ok?”

She shook her head vigorously, unable to speak over the effort of trying to breathe.

“Do you want help?”

She nodded quickly, in a panic.

“My name is Paul. I know what to do. Are you ready?” She nodded again. I took off my mask, grabbed her by the head, and leaned in closely. And I started breathing hard on the icicle, exactly as Justin had done for me. After four or five hard blows there was no sign that the ice goober was softening. So I stuck out my tongue and started licking it: It was as hard as a rock. Then I sucked on it like a thumb-sized snotsicle until it cracked free and fell away. Instantly she took in a huge breath through the valve, with a great whoosh of air. After a few breaths her eyes calmed and she relaxed a bit.

“Thank you! I owe you a drink when we get to Kathmandu.” For me, this was a highlight of the day. As a doctor, I enjoy helping people, and until that moment on summit day I had been someone who needed help instead. Not a comfortable role for me. We chatted for a few more moments, and I discovered that she was with a good US guiding outfit who were right there with her—no doubt they would have realized something had gone wrong with her mask and fixed it on their own. Still, it felt good to be of assistance.

Moving up from the Traverse there were well-defined steps kicked into the snow. Although the route was steep, these steps made the going pretty straightforward. I had dreamed of the Hillary Step for years: solid, steep granite on the left, ending in a slab that had to be straddled or mantled over. And a snow cornice on the right, slipping 10,000 feet down the Kangshung face. Would I have what it took to climb it?

In fact, the snow steps just kept going up, and then eased off after about 40 feet. I had climbed the Step without even knowing it. In the weeks that followed there would be much made of this experience online: Why was the step so easy this year? Had part of it crumbled and fallen away during last year’s quake? Looking back at my photos, I was almost certain that the rock features had changed compared with prior years…. But there was so much snow this season that blanketed everything, making things easier than usual, and shrouding some details.

Actually, I paused briefly on the step to clean my goggles. They had become hopelessly fogged by exhaled moisture streaming up from the leaky seal across my nose, thanks to the broken head strap hook on my mask. Ishi was right behind me at this point, at least I think it was he who kindly offered me a roll of toilet paper to use to wipe the condensation from my goggle lens.

Shortly above the step I came across a piece of rope that I could not understand. The route moderated, and for a short distance of about 20 feet it was almost dead flat. The line here was unrecognizable: thin, white strands like gossamers of kite strings… the ascender passed easily over them, although there was no way these strings would hold a true fall. The exposure to our right was zero (you would have to climb up and over a cornice to fall down the Kangshung). On our left, the slope was also quite gentle: You would have to work hard to fall here. So, this was not a problem.

It was only later, on my way down, that I realized what this was: The inner core of an eroded rope, the kernmantel totally gone. This line had been in place since at least 2013, if not earlier, because we were the first climbers to make it to the top from the South Side since then. It had been frozen solid, whipped by the wind against bare rock over and over again, hour after hour, year after year… and now the core was exposed to the full force of ultraviolet radiation at 29,000 feet. And, still, it held together.

The terrain above the step is a series of gently rolling snow ridges, each looking like the others. Nondescript, except that their sastrugi were exquisite, a chiaroscuro of compacted powder and sharp shadow that I have come to love over the years. When I see snow like that, etched by the wind into otherworldly beauty, I know I am really mountaineering.

I knew we were close, but had read of so many climbers being disappointed or heartbroken by the agony of that last stretch above the Step. I wanted to use my brain, to focus on the math: It’s less than 100 horizontal meters to the summit. Less than a football field. I dared to look up, just once, and there it was: a cornice in the distance, leaning out over Tibet, with strands of prayer flags hanging loosely. You are almost there. Just focus. One step at a time.

On every major summit I have experienced a transcendent flood of emotion just below the top. At the moment when I realize I am about to make it, that all the anxiety and planning and exhaustion are about to pay off, the wall that holds back my hopes and aspirations falls, and I am overcome with a wave of relief and joy—pure, raw joy. Tears roll down my face and I fold at the center, collapse, and surrender to the moment. Not endorphins, not a postoperative narcotic fog, not the intoxication of alcohol, not the release of orgasm… all that is bullshit by comparison. This is the same joy that seized me when my children were delivered—every cell, every blood vessel, every nerve ending, every crease in my brain alive and thrumming and grasping me, possessing me, shaking me like a toy in the jaws of a monster, a helpless witness before the monumental truth that no one could ever deny: YOU DID IT. YOU MADE IT. YOU EARNED IT. YOU ARE ON THE SUMMIT. At these moments I feel profoundly close to my family, even if they are half a world away. They are with me, holding me, kissing me, encouraging me, congratulating me. We are united, and I bask in their adoration and affection. They understand why I do this, and all my transgressions are forgiven—the time away, the attention I have paid to the mountains instead of to them. They know that I love them, and no words are necessary. We are one.

But, not on Everest.

On Everest, there was just one thought: When will we reach the summit?

I was aware of every step, every movement of my hands, every breath. I focused on the work. You can do this.

As the ridge rose gently higher, it gave way to subtle waves of snow and ice. The sastrugi were thrown into sharp shadow by the sunshine. The sky was perfectly clear. On our left, the mountain dropped away to a totally new landscape: fierce, dead, brown, like a crumpled sheet of butcher paper sprinkled with a bit of confectioner’s sugar. The Rongbuk. On our right, the cloud plume ripped away and fell down, and in the distance the high plateaus of Tibet were visible for miles and miles. It was beautiful.

And holy cow, was I tired.

Pasang Kami looked like he was getting cold. When we were within sight of the summit, he walked ahead at his own natural pace, which was faster than mine. I did not blame him for pulling ahead. Besides, Justin was only a few steps ahead of me.

In the last steps leading to the summit, the mountain’s pitch moderates further, the ridge widens, and a cornice separates us from the 10,000 drop down to Tibet. The fixed line stops about 30 meters from the summit. The chances of falling there are slim… but the consequences would be deadly. When we reached this final anchor, Justin silently turned around and unclipped my safety, then clipped it to his. We walked those last steps tethered together. He was being paid to get me up and back safely. And this was his seventh time on top, which must be some sort of record. He was my guide. I was profoundly grateful for his hard work. And I hoped I had also earned his friendship.

No mistaking this summit for anyplace else in the world: A mass of prayer flags draped over the small snow-covered pinnacle… a view stretching over 100 miles in all directions… bitter, bitter cold and wind… searing sunshine… faceless climbers in oxygen masks and down suits. Just a few steps more. Just a few more to go….

When he reached the top, Justin unclipped my safety from his, turned around, and gave me a huge hug. We’re here. I thanked him and shook his hand over and over again.

Steven looked good up there, sitting down and relaxed, happy. He had arrived shortly before me. We hugged quickly and I put my pack down near him.

Pasang Kami seemed comfortable as I grasped his hands in mine and bowed my head to him in a gesture of thanks.

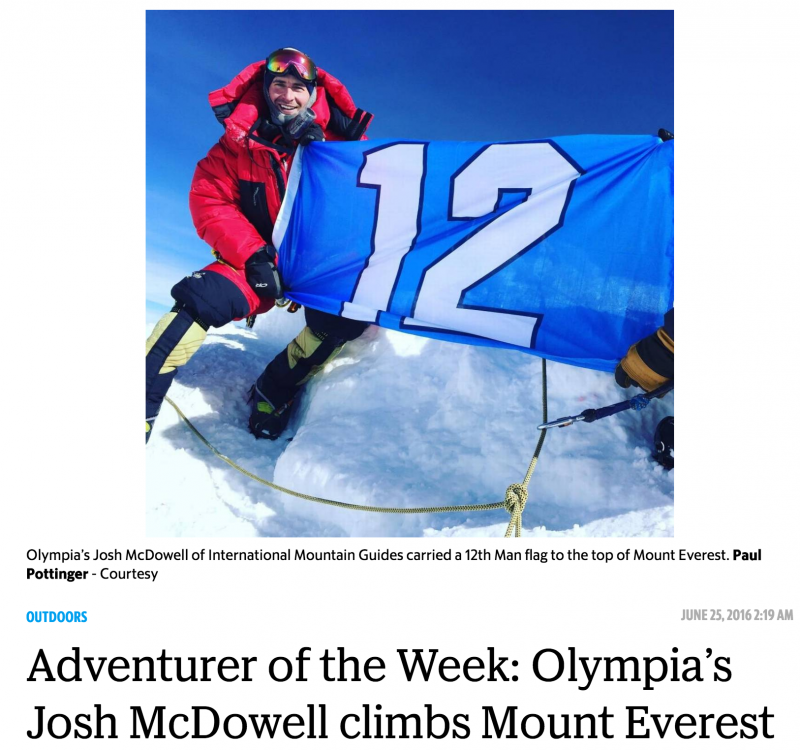

I realized that Josh was right there, too… hard to mistake him for anyone else in a Seahawks hat! He insisted on a photo of him and Justin holding a 12th Man banner, which I was glad to snap. We hugged happily. He said, “Seems like every time I summit a new mountain you are there!” I had forgotten that climbing Aconcagua had also been a first for both of us.

I was thrilled to be on top. And I indulged in moments of happiness. I smiled so broadly that the seal on my mask broke, and a puff of raw air scooted across my cheeks, freezing every whisker soaked with condensation and sweat. Justin offered to take my photo while I knelt down on the summit.

I fought back tears when I held up the photos of my family. I felt that they were with me.

The picture of my brother Matt holding my son, Matthew, taken years earlier. This is for you, Matty.

The picture of Doug Black that I took one fine winter day in the Cascades. “Hey,” Josh said, “That’s Doug! I know that guy!”

“Yep, because he’s awesome. We miss you, Douggie Fresh.”

An inspiring photo of kids from the Shining Stars Foundation, a group that teaches kids who are battling cancer how to ski.

A lovely photo of my buddy Blake with his adorable daughter Charlie. “Wish you were here Blake.”

And I almost broke down when I held up the photo of my friend Gene. I’m so sorry, buddy. I should have visited you before you died. I’ll try to make it up to you. I’m trying right now. The top from a bottle of beer he once gave me was right there, wearing a hole in its mesh stuff sack. I’m so sorry….

I had planned to talk to Julie, but it was simply too cold to try to operate the sat phone. And I was too tired to use it. Instead, I forced myself to swallow some water and eat some sport beans. I was vaguely aware of the badness that was happening in my kidneys: I had drunk little water and made zero urine all day. And yet I had no thirst at all. Just a few more swallows… do it.

Time is strange on the summit: I was busy making sure that I got the photos I wanted, and time flew by. I can see on my GPS track that I arrived on top at 7:30 AM, and left about 50 minutes later. It felt like I was up there for only 15 minutes.

This moment had been a dream for me since the second grade, and a focal point of my life for the last nine years. I had envisioned myself standing on the summit so many times, with such clarity, that my fantasies of it felt almost like memories. If ever there was a time to break down, this was it.

But a primal part of me kept that wall up. Keep it together. We are literally, exactly, precisely HALF WAY DONE. And based on the way I felt, that was not good.

I was cold and profoundly tired. Descending to Camp 2, 6,700 feet below, seemed a very challenging task. I began to break the descent into sections in my mind, to plan for the coming hours in discrete portions.

However, I did not actually know what the following hours would hold for us. Pain and exhaustion for sure. That was part of the plan—I was ready for it. Looking back a year later, it is clear that I was not psychologically prepared for the story that would unfold: The testing of my stamina, down to the core. The heartbreak of crossing a dead climber. The horror of hearing others while they lay dying. The PTSD that chews away at the fringes of the fabric of myself, like moths gorging themselves on an ornate cashmere carpet. The catastrophic truth that will never go away, no matter how many times I replay the day in my mind, no matter how clearly I can see that their fates were sealed, no matter how hard I try to ignore it, no matter how I deal with the flashbacks, no matter how many times I wake from the nightmares, and no matter how much whisky I drink: You didn’t turn them around, and now they are gone. Their children have no fathers, their wives have no husbands, their parents have no sons. And it’s on you.

Standing on the summit I had no way of knowing that the descent would test me in these ways. I only knew one thing: GO DOWN. SAFELY. NOW.

I’ve been waiting for this Blog entry for weeks! Thank you for sharing your awesome story with us.

Thank you Phil.

Wow oh Wooooowwww….. what an incredible adventure, and told so well, I almost felt as though I were there (from the comfort of my armchair!!). Thanks, Paul, for sharing your most memorable experiences with all of us…. what an astonishing set of words and photos!!! p.s. Thanks also for the FOP logo, I loved that beyond description, heh heh…. FOP ’till you drop!

Wow Paul…what an amazing account of your summit day. I could not put it down until I finished this morning. Thank you for sharing this with everyone. Your writing is a true gift.

Thanks Jeong. Working on the final three installments now… it is tough. Glad you enjoy these posts!

Thank you so so much for sharing your story with us armchair “mountaineers.” I sincerely hope you are able to quiet your demons if not to put them to rest. Best wishes to you!

Thank you Christine, this is lovely.

Thank you Paul for this riveting account of your ascent. Great to see FOP represented at the top of the world!

Thanks David! FOP is forever….

Paul – Your writing is brilliant! I’m sharing your blog with my family and friends because I could never describe the climb in the vivid detail that you seem to so effortlessly do. Plus the photos are spectacular! I climbed with IMG in 2013 and I noticed in their updates during this season they used many of your photos. Take good care.

Thank you so much Doug, this means so much coming from another summiteer!

Hi Paul,

We’ve been patiently waiting for this installment and oh boy has it been worth waiting for! As always written from the heart, frustrations and feelings openly expressed with huge amounts of detail about the climb. Truly a great read and without doubt some of the best Everest photos ever. We having been following this years Everest season with great interest, but it’s your story that really grabs us. Really looking forward to the next episodes, but also intrigued to see where else your adventures take you. Inspirational.

Thank you both so much, I am delighted by your kind feedback and encouragement. More to come soon….

Paul,

Congrats on making it to the top! Thanks for sharing your great story and the great pictures. Looking forward to the next episode.

Dan

Thank you so much Dan.

Amazing! I’m enjoying your adventure second hand, thank you for writing this. And the photos are spectacular.

Thanks Tara! Glad you are liking this. I appreciate your interest.

Just finished reading and my heart is pounding. Your writing is amazing Paul. I felt like I was there with you–alternately terrified and elated. Your story had me burst out laughing and burst into tears. I am so freakin proud to be your sister!! Your drive to be your best self is incredibly inspiring. Wow. Now please tell me where I can send a fruit basket to Justin Mearle!

Katie, I brought fruit for Justin (and Paul) when they arrived at SEA-TAC last year!

Love you sis. Thanks so much. For everything. I was proud to carry your pic to the top of the world… you deserve that and more. I love you.

Paul: this is great writing, thrilling and heartfelt! I am on tenterhooks waiting for the next installment. Meanwhile, as we used to say in (Anglicized) Latin: “illegitimi non carborundum” (don’t let the bastards grind you down), whether they are others or of our own making.

Thank you Nelson, in all ways… always.

Really glad that you are able to continue posting and congrats on the summit! Thought you stopped the blog because you got a book deal or something. Absolutely love your writing style and your pictures are fantastic. I will be doing a couple Mt. Washington winter climbs this winter and then my first Rainier climbs next summer.

Thanks so much Tim. No book deal… yet. No, slow in writing because it is painful to me to think about the losses that rotation, but writing is helpful, and I greatly appreciate your support, thank you.

Yes, Justin Merle has been to the summit of Everest 7 times, and each time we have searched the web looking for every bit of news we could find about how his trip was going. 2015 and 2016 were different; Paul Pottinger was blogging! For the first time ever, we could follow the trip in exceptional detail with magnificent pictures to capture the majesty of this mighty mountain and the efforts of those who dare to conquer it. The bonus for us was that we could see Justin “doing his thing” in many of the photos. Your blog wasn’t just a description of climbing the world’s tallest mountain, but a passionate accounting of your thoughts and emotions as you gave it your all. So we thank you, Paul, for taking us along with you (and with Justin) to the top of Mt. Everest! We congratulate you on your summit! We thank God for your safe return to EBC and to your family in Seattle. We look forward to reading about your trip down the mountain.

Karen and Bruce, thank you so much for this kind message… and for raising such an amazing son, too! More to come soon…..

We have spent countless hours with Kim (aka Atomic Girl) and Steven telling us of their mind boggling adventures. We were so grateful that they could summit together. We will never truly be able to understand what you guys endured but the blogs the three of you have posted paint a vivid picture of the climb and it’s many gut wrenching moments of fear, doubt, and the utter thrill of reaching a goal few people will ever experience. Congratulation.

Thanks so much Mike and Caryn for this lovely message. Your kids are amazing… thanks for spawning them.

Hey Paul, I came across your story rather by coincidence but had to read it all at once. Very talented writing and great physical and mental achievement. Huge respect to you for all of it!

Thank you so much Clemens, this is really lovely to hear and I am glad you found the blog. Please feel welcome to share with anyone whom you think might be interested.

Paul, You are one of the most talented people I have had the pleasure to know. I don’t know you personally, but I feel like I do from the beautifully composed photos and writing so descriptive that I cannot put it down. Because my brother, Roger, was with you for part of the climb, I was privileged to read your blog. I wish that you could make it into a book – such a treasure. Thank you for sharing you most personal feelings and thoughts with all of us. Yvonne Sage

Thank you very much Yvonne, I really appreciate your kind words and your interest. Working on a book now, so stay tuned….

Thank you so much for sharing your adventure with all of us! I have been close friends with the Hess family for 20+ years and was so excited to follow their progress via your post’s. Your blog entries and pictures have been absolutely amazing! Thanks for wearing the GPS tracker too. I was glued to my computer refreshing my browser constantly the night you guys made your bid for the summit. I was getting really worried when you were headed down and it seemed to take forever. I’m glad everybody made it home safely. Congratulations on your accomplishment!!!

P.S. Did you ever get your GoPro working?

Thank you David, for all of this. Yes, I shot the whole Southeast Ridge. Editing now in process….

Yay, I’m really looking forward to seeing the footage!

Wow really well written Paul. I think this is the most honest account I have read on an Everest Summit. From now on when I am doing a systems check prior to attempting a summit I will check “My genitals are lined up correctly” too funny.

See you up high some time.

Line ’em up or lose ’em.

Hey Paul. Great blog! Just found out about it 2 days ago and read through the entire Everest experience. Felt like I was there! Thank you so much! I was wondering if you’d mind if I print the picture of the Everest shadow on the Earth and put it up in my office? I think my patients would really enjoy seeing it.

Cheers!

Thank you so much for the footage of Khumbu Icefall and the writing. So vivid and real! For past three days I have watched maybe 24 hours of Everest footage, but your traverse of Icefall was spectacular! Would love to know more of how was the descending.

Thanks so much. You can learn more about the descent here… http://pottinger.net/osm/2017/06/down/ The rest of the descent will wait for our book, hope to have it out in 2019!

I LIKE A LOT OF THIS PAGE. QUESTION SOMETHING THAT NOBODY HAS ASKED .. AND ALWAYS I HAD THAT CURIOSITY WHEN WE ARE IN HEIGHTS OF MORE THAN 8OOO METERS WHICH FEELS THE HUMAN BODY AT THE LOW ADMODPHERIC PRESSURE SINCE THE NORMAL PRESSURE, AT SEA LEVEL IS 760 mm Hg .YA 8000 MTS IS DXE 267 mm Hg. Could you tell me some experience of what it is like to feel such low blood pressure?

Thanks. Hypoxia makes the blood pressure rise, actually… this is what causes the headaches, and potentially complications of HAPE and HACE. So, how does high blood pressure feel? Rotten! Headache, exhaustion, etc. It is a tough climb for this reason.