The day’s climb, condensed to 13 minutes. My favorite segments are at 3:44, 5:00, and 9:42.

For those who want to see all the footage I shot that day, about 2 hours of our 14 hour day, here it is. Language cleaned up, otherwise raw footage:

Here’s the blog.

I slept well on the bivvy ledge. The sheer drop to my right focused my attention as I got situated in the bag at bedtime, because a row of stones several inches high separated me from the void. But, I’m not a roller / thrasher at nighttime, and I knew I’d be fine. I surrendered to dreams of work piling up in the hospital… then the faces of my family… then the steep ramparts of Forbidden… then the crevasses we had passed on our way to the ridge. I was walking on the ice, threading my way between the dark, bottomless cracks… then the ice became gyri of a giant brain, and the crevasses were sulci separating them. I felt the electrical activity of thoughts coursing through the massive tissue, rocketing silently to and fro, carrying messages I could not understand. I often get freaky dreams in the mountains..

Several times during the night I heard scurrying around my head…. Mice? Rats? Pika? Snafflehounds! Justin had told us of the presence of these marauding miscreants, alpine mischief-makers that love to eat anything and everything available. We had left our bear canisters at low camp—no bears up here!—and this meant that only plastic and fabric separated our food from the hungry rodents hiding among the bivvy stones. I kept my food in the sleeping bag with me, where it was totally safe. But, circle my bag they did, and several times I shooed them away. Nothing to eat here!

Morning revealed the toll these scallywags had taken: My trusty Creon Light 45 pack was destroyed. Tiny teeth had chewed the back ventilation mesh away from its anchor points on both sides, leaving it to hang uselessly. Dammit! Snafflehounds! Whether they were actually rats or mice I will never know. They must have been after the salt from my perspiration that had caked there yesterday. The pack would still work, but it was seeing its last expedition. I thought about the first time I had taken it up high, to the top of Mont Blanc with Matt and JR, 7 years earlier. I had beaten it up badly since then, and had sewn rips closed so many times that it started to look like Frankenstein’s monster. Now, this was the last straw. Farewell, sweet Creon, you served me well….

We were up at 6:30 AM, and the dawn revealed a spectacular, still world. The smoke was not too thick, but it turned the East into a band of rich orange light. The North Cascades stood in sensational blue and purple tones. A white crescent moon added to the dramatic look. The North Ridge stretched away towards the summit block, which looked impossibly far away, and so high above us. And, the vast emptiness of Forbidden Basin was revealed for the first time. All of this had been hidden in the darkness when we arrived the night before. I have never overnighted on a big wall, but I suspect waking up on a portaledge feels something like this.

Justin started boiling water while Ann and I got ourselves together. Sleep had restored my energy. Everyone felt good. We marveled at the world around us. There was even time and space for a bowel movement. Posh, indeed. We were ready to get moving by 8 AM, right on schedule.

One of the more objectively challenging obstacles presents itself minutes after leaving camp: A gendarme tower rises steeply from the gentle slope of the ridge. There is no way around it, on either side. It must be surmounted. We watched Justin as he led the pitch up a half-chimney, which involved finding hidden footholds, stemming, and mantle moves.

“How does he do that?” asked Ann.

“Piece of cake.” Because this was the steepest section of the ascent, Justin belayed us up one at a time (much of the day would involve simul-climbing.) Parts of the pitch seemed devoid of reliable handholds, but of course they were there. I was out of sight from Justin and Ann, but they could holler down advice at just the right moment. “Reach up with your right hand and feel to the right, there’s a good hold there.” Son of a… there it is. Getting this obstacle out of the way early was a relief.

The North Ridge is punctuated by a series of towers, or more precisely by steep sections several hundred feet high, intermixed with low-angle terrain. The entire climb seemed unthinkably immense, so these steep aretes made natural sub-goals to focus on. As the crow flies, the whole day was probably under a mile in distance, although my GPS ended up logging 1.3 miles. Just a mile… how hard could this be?

The climbing was spectacular. Not too difficult, but requiring full focus. Coordination of hands and feet, stepping and reaching in sequence, minding the rope between us all the way.

Initially, for the first several hours, the ridge was relatively wide, and we often climbed to one side or the other, in effect traversing. In some places the terrain sloped gently down to either side. But as we gained elevation it became much narrower, often several feet across at most, and the drops were very exposed. In other places the ridge was simply a thin fin of rock that we gripped at eye level while traversing, like the peak of an impossibly tall A-frame house. At one point the ridgetop was genuinely sharp for about 12 feet, like a giant flint knapped into a blade. Justin was able to scootch along it resting on his perineum, which worked for me too. Ann, not so much. She tried to rest her weight on the ridge for about half a second before stopping. “Nope. No way. That’s not happening.”

“You could ride side saddle—“ I offered.

“Nope. We’re done.” Ann stepped out over the void and shimmied along, using the ridge like a railing. Exposed, but dignified, and definitely better for her anatomy.

Of course, Justin always had us on belay. When the terrain was modest we moved as a team, protected by the rope threaded between horns. But, this was not always possible. The ridge rises unevenly towards the summit, in a series of towers, each higher than the last. Some of them take minutes to climb, others closer to an hour, or longer. Justin would usually lead out while we kept him on belay, then he would return the favor while Ann and I climbed together to him, separated by about three meters of rope.

Objectively, none of these moves was very hard. But the overall experience was indeed challenging. Synchronizing our moves while simul-climbing was just part of the difficulty. We carried packs weighing about 40 pounds. The rock’s stability was unreliable, and every hold had to be tested. This route is rarely climbed, so nothing is worn smooth or tramped down. Feeling for small features in the rock through my mountaineering boots was totally different than in rock shoes. The sun blasted down, casting harsh glare and throwing deep shadows. Sunscreen tended to run into my eyes where it stung. Or, was that the wildfire smoke, which was also triggering post-nasal drip? And the exposure was spicy… hundreds of feet (or more) to the glaciers below. No, the moves were not that difficult, but the overall experience of alpine climbing was so far from climbing in a gym as to be almost unrecognizable. Don’t get me wrong: gym climbing is amazing, I love watching it and aspire to get better at it. About damn time it is becoming an Olympic sport. Still… this ain’t no climbing gym.

Mountaineering requires full focus, which suits me well. I am not innately gifted at multi-tasking or thinking strategically. I have to do that in my administrative roles, and I don’t mind it. But, the single-mindedness required in mountaineering calls to my true talents, in the same way as clinical medicine: Here is a problem that I can see, touch, smell… If I just put my mind and my whole heart into this, I can solve it. I will figure this out. Certainly, mountaineering is all about solving problems, great and small. But, there’s more to it than than. At a break I looked past my boots dangling in the air, down to the turquoise-colored tarn far below. I reflected on why I had chosen this hobby: It’s beautiful… challenging… inspiring. And on Forbidden’s North Ridge, it is also hazardous. I climb in spite of the danger, not because of it. Right?

Maybe the hazard is part of the attraction. Twenty-One Pilots’ lyrics came to mind: “Death inspires me like a dog inspires a rabbit.”

The ridge was bone-dry, except for two snowfields. We passed the first one soon after leaving camp, and decided to press on to the upper snowfield rather than stop for water so early. This was the right decision… I drank the last of my water just before we reached that upper snowfield. It was an ideal spot for a break, because we were protected by a stone wall on one side, and the snowpack on the other. For the first time in hours we could untie, get the boots off, take a leak, eat food, gossip… be human again. The stress of the exposed ridge melted away, and for half an hour we were just three friends enjoying the outdoors, like on any other trip.

Gearing up after the break, I felt pretty good. Hydrated, nourished, not sunburned… it seemed we had plenty of daylight left. We were moving slowly but steadily, and with total protection thanks to Justin. We were climbing the North Ridge. Let’s do this.

I climbed just fine. At one point I was deeply disappointed in myself for failing to clean one of Justin’s cams. We were on the west side of the ridge, in deep shadow (a momentary blessing), on a section of vertical rock punctuated by standing platforms filled with loose dirt. There was just enough of a foothold for me to balance and grab the cam’s handle… but the jaws just would not move. Not a millimeter. Goddamn it. I wiggled it gently, shook it, tried to slide it to and fro… Nada. I told Justin I was out of options, and confirmed that the cams were no longer moving. He told me to leave it, and I apologized profusely. he did not seem perturbed, not even a little bit. “It happens, no worries.” But I still felt badly.

We could see people on the summit above… they looked so close. But it took hours to reach the final pitch, because we climbed carefully and with solid protection the whole way.

My GoPro-6 failed to capture those last pitches, which was very disappointing… it was brand new. Removing the battery on the summit seemed to reset it, and I was able to capture most of our descent that evening.

The top of Forbidden is a tiny outcrop, just big enough for me and Justin to share… Ann found a tiny perch several feet away. It was warm but not too hot, with a nice breeze. The wildfire smoke was mostly below us. We could see for miles in all directions, including back at the route we had just climbed… and the way we would have to descend now, via the West Ridge. We grabbed a quick snack and water, mindful of the late hour. We needed to hustle, but it was sooooo beautiful.

I drank the summit in, and thought of Julie and the kids. I wish they could see this. I thought of work. What was happening back at the hospital? It was almost 6:00 PM on a Wednesday… case conference and board review would be wrapping up, and the fellows would probably head out for celebratory drinks. The next day, when I got cell service again, they texted me this photo taken while we were descending the West Ridge, confirming my suspicions.

It was time to descend.

Now it was my turn to lead. Instead of watching Ann’s moves, she had to watch mine. I needed to be sure my pace was slow, steady, and predictable, lest I pull the rope taught between us. Justin kept us on belay while we simul-climbed, then we would set up a rap station using a cam or simply by slinging the rope twice around a horn. Eventually we came across several proper rap stations, and clipping to those was very reassuring.

Initially the route was very austere: Totally exposed on either side of the ridge, which was narrow. In some cases it was possible to traverse on one side or the other, but usually the best option was also the most intimidating: directly down the spine.

When I found the first rap station I clipped in, and Ann joined me moments later. Justin descended carefully, and we had a few minutes to take in the scene. The sunlight light was warm and cast the ridge in a red hue, made more dramatic by the wildfire smoke below. It was going to be a beautiful sunset.

And then it would turn to night. And we would be forced to continue the descent in darkness.

Benighted. Fuck….

Justin had climbed this ridge multiple times, as had Ann. We would be fine. Still, I felt badly having to put on the headlamp, because it meant Justin would have to work that much harder to get us down. Be careful, smooth, and efficient. No rushing. Indeed, there was nothing else to do.

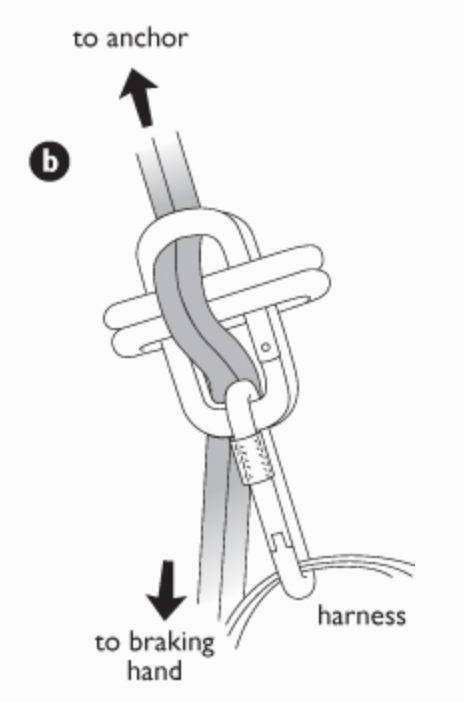

Justin joined us at the rap station, where we clustered together tightly on a slightly awkward perch and got ready to rappel the 50 foot face below. And we realized that Justin’s belay device was gone. It must have gotten hung up on one of the crags he had scrambled down below the summit. This struck me as a big deal… I had rapped on a Munter hitch before, and it added a jillion twists to the kernmantle, which was a total pain. Justin had a better idea, and was unfazed. When it was his turn to descend he simply rigged a 4-biner brake, like one I had seen in Freedom of the Hills years earlier. And it worked perfectly.

But, first I had to descend the tower. We could have thrown the rope down ahead of us then rapped it, as is customary on most Class 5 routes. However, that would have been a mess here, because there were low-angle sections and horns that would have snagged the butterfly coil as it sailed down. It would have been a pain. Instead, Justin lowered me directly, which was easy and quick. An odd descent for sure, switching from high-angle to gentler terrain, meaning I was half rapping and half scrambling. But it worked well. He then lowered Ann on the other end of the rope, so that when she reached me both strands were safely down the route, and he could rappel smoothly.

The sun seemed to hang in the West for a long time, hovering over Mt Torment like a big old lightbulb. Inevitably, we fell into shadow, and the chill of the evening quickly set in. Adding a layer and switching into the Hestra gloves did the trick. I noticed how much better I felt than 24 hours earlier, when the glacier crossing had really knocked the tar out of me. Now I was fine. It was night, but we were all fine. This was no epic. We’ve got this.

Soon after nightfall the route plunged down to the right. We watched Justin’s headlamp become smaller and smaller as he rappelled the North Face. It was remarkably still. In darkness, the mountain seemed to change: It began to feel friendly, smaller, enclosed, as though the night became walls and ceiling of a private room surrounding us. I breathed—really breathed deeply—for the first time in hours. I forced my shoulders to relax, then my arms, then my spine. However, we remained exposed, and the sensation of enclosure was an illusion. Stay focused. I thought of Christian Reindl’s lyrics:

You don’t have to search for more

We’ve heard it all before…

You can’t fight this twisted fantasy

“A friend of mine”

I’ll wait for you to see…

Don’t try too hide

You know you’re better off with me

I’m the devil on your shoulder

I’m only cold so you’ll come closer

When you strain your eyes to find the light

I won’t be far behind

Cause it’s better in the dark

When you’re a friend of mine

It’s a hell of a ride…

You don’t have to search for more

I’ll give you what you need

What are you waiting for?

I’m right beside you, tearing on your sleeve

—Christian Reindl

We made slow, steady progress, down and down. The north side of the ridge grew wider, littered by car-sized boulders lying in a jumbled mess. Just before 10 PM I said, “Hey, there’s a big snowfield ahead.”

“YES!” cried Ann. She knew that the bivvy ledge was perched just above the snowfield. And, sure enough, it was. Atop a story-high wall were three platforms of earth, each totally smooth and the perfect size for a bivvy bag. Justin chopped some snow from the glacier into a garbage bag, then hauled it up to the ledge so we could melt water. I sent a text to George Dunn telling him we were at camp. Hot food… dry sleeping bag… a billion stars overhead.

Ann told me to turn out my headlamp and look south. I knew the ridge was there, and wondered if we could see it in starlight. As my eyes adjusted, I realized that the ridge was much bigger than I had guessed: It rose like a tall, evil pyramid towards the sky. “Holy cow.”

“Pretty cool, right? We climbed that.”

Yes, we did. Thanks to Justin, this summit had become a reality for me, and doing it via the North Ridge made it even better. Doing it with my friends was the best part of all. I thought of our other buddies who would love to have been there. A larger team on the North Ridge would be impossible, or unsafe at the very least, but I still wished they could have joined.

As I fell asleep, I thought about the Catscratch Gullies we would rap in the morning. But, only briefly. Enough climbing… put that monkey mind to sleep. I let all my concerns fade away. I hoped that my blue bag would help fend off the snafflehounds in the night. Even shrouded in three plastic bags it smelled simply horrendous.