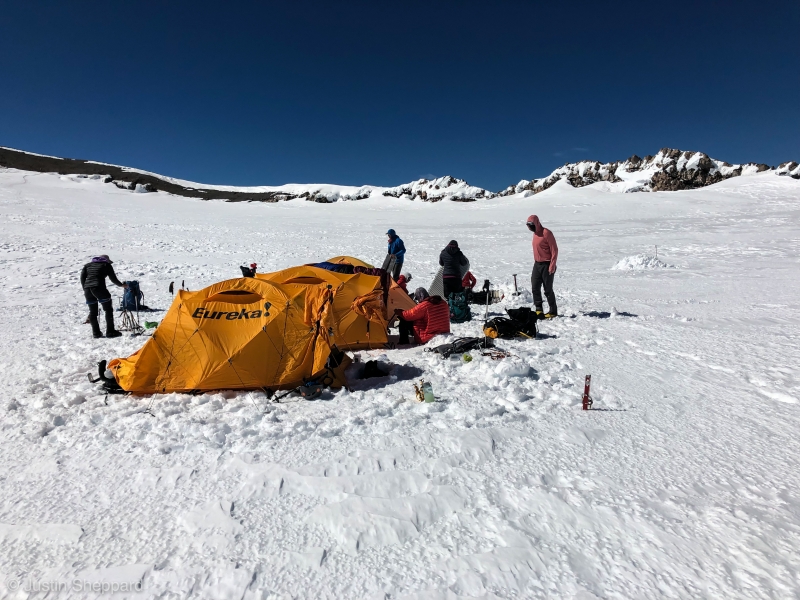

That night I tossed in the sleeping bag, made a bit of urine, dreamed of the route, adjusted my layers when chilled… I slept in total for a few hours. Another party passed by quietly circa 12:30 AM, but otherwise there were no surprises that night, except for the tent getting buffeted by gusts of wind that felt slightly ominous.

The wakeup call came at 2:20 AM, which seemed perfect to me.

We got right to business by packing and simultaneously eating a quick breakfast of oatmeal and instant coffee. My bowels were quiet, no need to visit the latrine except to empty the cold, gnarly looking contents of the pee-squared bottle. The ominous breeze turned out to be no big deal—actually, it was surprisingly warm outside. Our blue bags remained squishy and fragrant in spite of being buried in the snow since before bedtime. Breaking camp went fine… the usual chaos of getting packed up in the dark was no issue, and we were more efficient than the prior day. By 3:55 AM, 90 minutes after waking up, we started walking.

Conrad, Teresa, and I left Camp Hazard third in line that morning. While we waited for our buddies to ascend ahead of us, I looked to the East… and there it was: A deep burgundy sunrise beyond the Muir snowfield. No sign of clouds aloft… katabatics only, no true wind… it would be another spectacular, clear day. Just as forecast. Can we make it out of the Chute before the sun hits?

Our first objective was the Sneak, an unofficial, unmarked transition point between the Turtle and the Kautz Glacier. The rocky ridge that separates these two snow features can be down-climbed in a variety of locations… you can even do it right from the kitchen at Camp Hazard. But, our guides knew the ideal spot, a small rocky step that allowed us to “sneak” onto the Kautz without much fuss or hassle. And they had intentionally set camp just a few minutes below it.

The Sneak was a jumble of dark volcanic rock that jutted out over a very steep snow face that fell away for hundreds of feet. This is the Kautz Glacier, finally revealed. The step was not high—perhaps 20 vertical feet—but the exposure to the snow face below was spicy. This was a no-fall zone, for sure. At the bottom of the step a narrow catwalk of snow abutted a tall rock cliff on the right. This catwalk led up and away, towards a broad, open section of glacier above. We stayed warm and snapped photos while waiting for our teammates to negotiate the step. The dawn brightened, revealing our volcano neighbors in the distance: Klickitat, Wy’East, and Loowit.

The Sneak formed a bottleneck: Each of us had to down-climb it one at a time, protected from above by a belay set by our guides. Well, not really one at a time… we were tied together at a couple armspans’ length, so this turned into simulclimbing after the first person was halfway down. Just like Forbidden. A stout static rope was fixed in place, which we could use as a hand line. For me, this was a dream come true: I trusted the hand line 100%, leaned out into space with my arms straight and relaxed, and focused on my footing. Plenty of fine footholds revealed themselves. Most people hate rock climbing in crampons, but I kind of like it. Anyone can climb in shoes… crampons make it harder, especially in the cold of morning, carrying 40 lbs, at 11,000 feet, with just a couple meters between you and your partner on the line. How fun is this?

Teresa and I reached the snow ramp, plunged in our axes to their heads, and waited for Conrad to join us. He down-climbed smoothly without a top belay, then passed above us in an awkward transition on the catwalk. Once again, Conrad was in the lead, T took center, and I brought up the rear. We traversed up and to the left, crossing a portion of the Kautz Glacier. This was a wild place, for sure. Directly above, the mountain was littered with icefall spilling over a band of rotten, chossy rock. Up to our left, beyond the West side of the Chute, another stone face rose towards the sky, band after band of brown rock punctuated by layers of snow and ice, undeniably reminiscent of a chocolate layer cake with vanilla frosting. This must be the Kautz Headwall… the feature I had planned to climb this season with a friend, although our arrangements had not worked out for several reasons. Climbing via the Kautz Ice Chute instead now seemed like a wise move for my first time on this side of the mountain. And, so much fun to be a part of this expedition with these teammates.

When we reached a slightly more stable position on the face, Conrad adjusted our rope interval, in light of the steep stuff to come. Below, in the distance, our shadow stretched across the dark green land and pale sky.

After a short time we were finally on the Kautz Ice Chute: a steep, triangular snow ramp, bound on two sides by compact snow ice. The walls were dirty, complex, and tortured by snow-melt cycles into penitentes and sun cups. Even at its narrowest point at the top, this was exponentially wider and more open than the Pearly Gates of Wy’East. In fact, it looked like we could just climb right up the center of the snow field, which seemed like an obvious, direct, seductive option… although I had to admit that it was littered with lots of recent slides. Maybe the penitentes are a better option.

The Goonies and Rowers of Rowan went left… teams She-Wee and Big Agnes went right. T and I watched Conrad start up the ice. The slope was not vertical, more like 60 degrees for the most part, and he threaded a route between the ice spires with ease. Then, it was our turn.

Teresa and I climbed together, just a couple meters apart. This was so reminiscent of climbing Forbidden’s North Ridge with Justin and Ann, but here we were higher… colder… heavier… less exposed… and climbing ice. And those first few moves out of the gate felt very, very steep indeed. We labored in synch. The ice was still very firm from being in the dark all night long, and it usually took more than one swing to set the picks. Often, the best spot for my tools were Teresa’ foot positions… landing my tools into her feet would be a very bad move, for all sorts of reasons. I swung hard, and I never hit her. Not once. Afterwards, she told me that the most stressful part of the climb was imagining what would happen if she kicked me in the head, or peeled off and landed in my face. But T is a very strong climber. “Oh,” I said, “I knew you’d never lose your position. It never worried me.” I suppose she did all the worrying for both of us.

That first pitch really was the toughest. Conrad shouted encouragement from his belay stance above: “It moderates soon, trust me.” Sure enough, the face went from about 70 degrees to less than 60, I would guess. Still exhausting, but doable. As we reached Conrad at that first station, he looked at my Raven Pro and asked, “How’d it go with that thing?” I carried a Nomic in my right hand, but just the standard old Raven Pro in my left.

I caught my breath. “Yeah… it wasn’t designed for this, no doubt. But, it went fine!” I actually liked the long shaft, which allowed me to hook penitentes that would otherwise have been out of reach. But, as for really setting the pick in verglas… not nearly as useful as the Nomic.

While Conrad re-racked the screws I had cleaned, and got situated to lead the next pitch, we had a few minutes to take in the scene: Airy… open… wild. “Here comes another team,” I said, after spying a roped party heading right up the middle of the Chute. These were independent climbers who looked strong, and I’m sure they were very nice folks. But, damn… they could have used some pointers from IMG. Their interval was many, many meters, and often the rope curved below the followers in great oxbows of more than 10 meters. This is a real no-no, because if someone falls it will allow the line to get shock-loaded, and dramatically increases the risk of others getting pulled away with them. I recalled Nickel’s clear command from the prior day: “Never climb above the rope in front of you.” So simple….

We started up the next pitch: Smoother, less steep, easier to catch my breath. There’s something about setting the front points, trusting them, standing on them with full confidence that is so inspiring. The Baturas and Vasaks behaved themselves, mostly. I have big, wide feet. It’s not my fault, I was just born this way. Anyhow, it turns out that most mountaineering boots are not available in wide widths; some are, and I have found the ones that work best for me. But, when it comes to technical ice boots… not so much. The LS Baturas are fine, totally fine for general mountaineering and also acceptable on steep ice so long as I can shake out my feet periodically and allow arterial blood supply to return. I was careful to do this every few steps that day, and it worked out fine. This was definitely the highest, and heaviest, multi-pitch ice I have climbed. And it was amazing.

Another break atop this pitch, while Conrad set up and led the third pitch. Ultimately we traversed up and left until we were out of the ice and rejoined him on the snow above the chute’s bottleneck. The terrain here was steep, so Conrad quickly chopped a bench out for us to sit in. It was a beautiful place for a break. As we got sorted out for the glacier travel above, I looked down on the Chute we had just climbed. It was gnarly, steep, and very beautiful. The moment deserved a shaka, no doubt about it. I saluted the mountain, and thought of Lloren’s lyrics:

It’s a high I can’t come down from,

It runs electric in my veins.

A drug I can’t come around from,

And I know you’ll feel the same.

There’s a fire in my body,

And it’s burning up my skin…

A kind of fever and I can’t fight it…

Now the fire’s getting in.

Can you feel it? It’s just the start.

There’s no greater form of worship

Than this holy kind of prayer.

Every bruise and break was worth it,

Just to feel something so big.

I’ve been tempted, I’ve been tortured,

Just to taste what I want.

They can’t take my new religion,

I’ll only come on back.

I am restless, it keeps me breathless

And sets a fire in my soul.

I keep it burning, beneath the surface,

Until that fire consumes me whole.

It makes me needy, and keeps me greedy,

I fear that fire that I know.

Can you feel it? It’s just the start.

Welcome to the belay.

We were in the sun now, just perfect timing because the rest of the day promised to be steep glacier travel, no more ice climbing, which would make it easier to manage our temperature. The next objective sat in plain view: Camp Wapowety, a spot of snow atop a ridge of dark rock at the origin of the Wapowety Cleaver. That location meant lunch… and, if people felt baked, it could also be a spot to overnight. All we had to do was put one foot in front of the other, and we would make it. Beautiful, untrammeled snow on the upper Kautz greeted us, split periodically by crazy deep crevasses. The snow bridges seemed stout enough, and indeed they were. This section was incredibly beautiful, and very interesting because it brought a new view of the upper mountain into focus. Point Success, the false summit climbed by Kautz himself back in the day, grew closer and closer. The Kautz Headwall turned out to be just as steep as it had looked from below. The Cleaver seemed closer than it was… this is always the way up high, where terrain features provide precious little—or misleading—information about scale and distance. We made fine progress, and I guess it took us an hour or so to reach Camp Wapowety, which is just right.

By the time we pulled in, the pack felt heavy and I was ready for a break. We had climbed 2,000 feet since leaving Hazard, and I was starting to feel it. Lovely spot for a break: Broad, unobstructed views for miles and miles, and plenty of room to stretch out and eat, drink, and rest. A rock band served as a makeshift latrine. It was a bit breezy, but just a bit, and in fact I was able to get my boots and socks off for about 10 minutes. By the time I got them back on, the socks were dry and my feet had begun to burn in the sunshine.

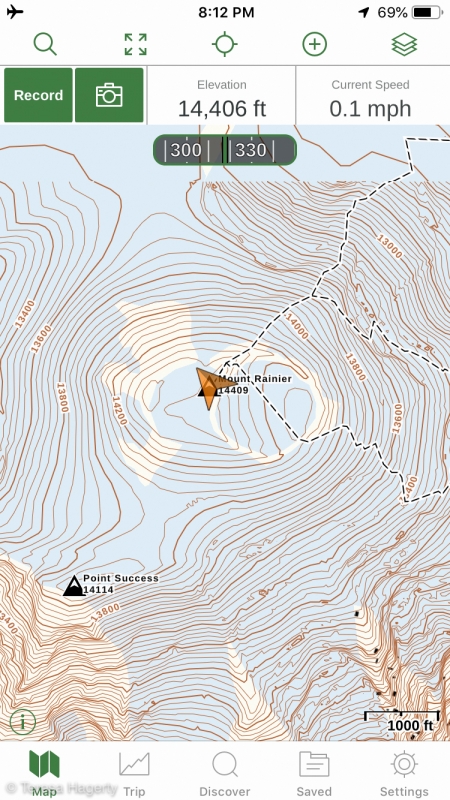

Behind us, the upper mountain awaited… we could see a rim of dark rock above, which must certainly be the crater rim. It looked close enough to touch, less than an hour away.

But, this was an illusion of course. Those last 1,200 feet are not easy. We navigated between seracs above Wapowety Cleaver, then began climbing the upper Nisqually Glacier. It felt familiar, so similar to my prior 5 climbs on this mountain… and, just like on the other two routes I have climbed, this one was deceptively long. When the guides called for a break after an hour, I was truly surprised. Food and water are always welcome, but I was eager to simply make the top. The crater’s just there…. Do we really need to take a break?

As it turned out, about an hour remained. During this final stage of the climb I allowed my mind to drift to a place it has gone before. As a child, perhaps 6 and 7 years old, I studied Barry Bishop’s photographs of Everest in National Geographic, and watched mountaineering documentaries on TV… I imagined the mountains as a foreign environment of snow, rock, cold, danger, oxygen cylinders, goggles, fear, joy, challenge, homesickness, and searing vividness—a vision so sharp and clear that it played like an Imax film in my mind. Often, in these visions, I was dying, or helping someone in trouble. All these decades later I sometimes have flashes of those early mountain impressions. They are not always disturbing, but… odd. And searing. When climbing Everest and other tall peaks, on occasion, I have seen myself from above, at oblique angles, revealing for a moment the context of our surroundings, and the audacity, even the madness—sheer, unbridled madness—of what we are doing. I usually shoo these visions away. Today, I allowed them to linger during the final steps to the crater rim. Mountaineering is joyful, but also painful, difficult, time-consuming… perhaps moments of introspection are part of the entire experience. The sastrugi were remarkably beautiful here—they looked exactly like the cover from Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures. The sky was an unexpectedly deep, unbroken blue. We are just minutes away from the Crater. Take it in.

I was the last expedition member to reach the rim. Everyone greeted me warmly. It was a wonderful feeling for everyone… and a bit odd, because what we all really wanted to do was get to the center of the crater and drop those packs! And so we did, picking our entry route carefully, for fear of plunging into a steam cave where snow met rock. The snow up here was smooth, and looked like a milkshake that had spilled and then frozen in place while dribbling along the floor. This was probably exactly what had happened, when volcanic steam had partially thawed certain areas which then froze again in the cold of the night. Anyhow, we tested every step, and all were solid. In minutes we made it to the far eastern side of the crater, and we were home. We had done it.

I was gassed. We took a short break in the sunshine, and I promptly fell asleep. This is a skill acquired during many years of medical training, and indeed is one of the cardinal rules of medicine: Sleep when you can. I snorted awake a few minutes later and realized that the guides were starting to build camp. In my haste to help I forgot to secure my foam pad, which a friend saved from blowing away. We stamped out a large rectangle, suitable for all 4 tents, and set to erecting them while the guides dug a kitchen and a latrine.

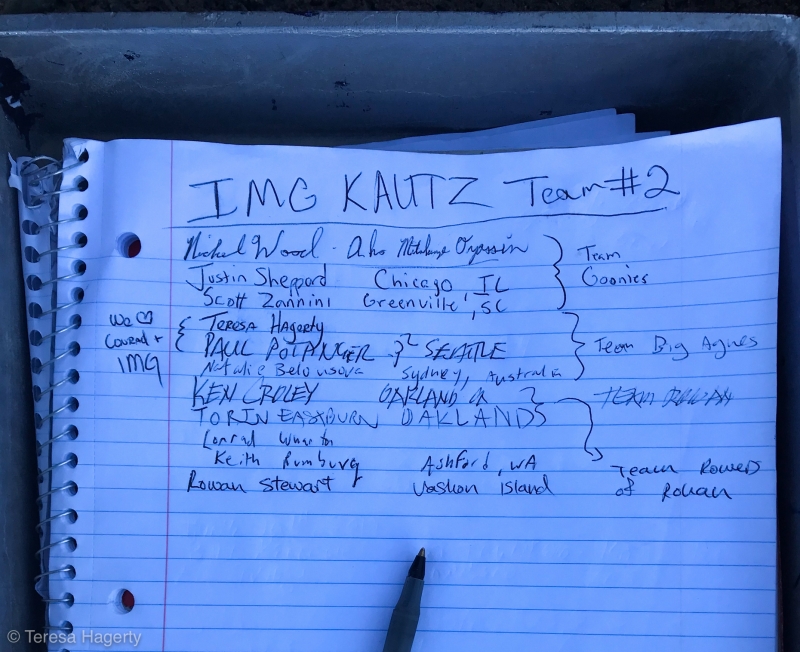

We had the crater and summit to ourselves that day. It was like a fabulous retreat, a private fortress in the sky. We enjoyed a delicious dinner of Thai noodles, and then lay down for a short time before heading to the summit, where we would watch the sun set.

It was cold crossing the crater, and the snow was very uncompacted, loose powder underfoot. We reached the main trail which stood a foot above the surrounding snow, raised up because it contained so much compact snow ice after being stepped upon by hundreds of feet that season, making it slower to melt than the surrounding powder. We made it to the register and signed in, marveling again at the delightful lack of sulfur stink here, so different from Wy’East. And then we went up to the summit proper.

Below, in the distance, human society raged on, in all its beauty and horror, simultaneously inspiring and despicable. The forces of stupidity and darkness continued to disenfranchise us, to threaten our health, to spoil our world in every conceivable way. And yet… there was good there, too. I thought of a speech I had given two weeks earlier, the commencement address at UW Med School, a great honor for me. The students were so inspiring, such a bright light to the world. I hoped that my concluding comments encouraged and inspired them, too:

“And now, graduates, please close YOUR eyes too. And focus on each of those same moments: When you realized you were going to medical school… meeting your classmates on the first day… sitting for that first exam… interviewing and examining your first patient… presenting your first H&P… nailing that differential diagnosis for the first time… spending time with your patients, listening compassionately to them, making a genuine difference in their lives.

That darkness that you see behind your closed eyelids is not emptiness, it’s a world of infinite possibilities and accomplishments yet to come. When you close your eyes at bedtime—and yes, you will be allowed to sleep during residency—what will you choose to see? When I go to bed I see my family, accomplishing great things… I see the mountains, tall, austere, so alluring… I see my colleagues—and that includes all of you—brilliant, energetic, dedicated… and I see the faces of my patients—both the ones I have saved and the ones I have lost. Each a unique person whose life I have touched in some small way—and who in return has enriched my life exponentially more so. I hope you will choose to see your patients too, and your incredible, inspiring colleagues. Being a part of their lives is a doctor’s unique privilege, a privilege each of you has earned.”

Above all else, I am a humanist. I believe that we can—and we must—do better. And no one, and nothing, will do that for us. I attended a Quaker grade school, and am now a devout atheist who is married to a non-observant Jew. And yet, I do think that some places are sacred, and I do have moments of spirituality. Perhaps MARS provides a more eloquent summary of these thoughts:

And I noticed…

I now know this:

In the end, there is no one…

There is no one to call your bluff.

In the end there is no one high above.

Who really can say there’s only one way to play the game?

In the end there is nothing…

There is nothing beyond the truth.

In the end there is only what we do.

Try, try as they may…

Running in circles with nothing to say.

See, only one thing’s for sure:

I’m not knocking on heaven’s door.

What’s up above, or underneath

Is not for man alone to breach.

Sometimes fail, and sometimes win…

With all the powers here within.

And I’ve noticed…

I now know this.

The sunset dazzled us in pure, golden light. Everything seemed to be lit from within: The tortured water ice underfoot, the shadows of sastrugi, Puget Sound in the distance, the strange cirrus clouds over the Olympics, even ourselves—we were glowing with happiness and pride at our accomplishment. We had climbed Tahoma via the Kautz, and now we had the summit as a reward. This was my 5th time on top of Tahoma, but never before at this time of day. I had seen this place at sunset so many times in my mind… and it had always looked this way. Precisely like this. In my mind, I’ve seen this before. The pain of the next day’s descent… the agony of driving home while exhausted… the challenge of seeing patients first thing after I got home… all could wait, out of mind, for another time. For now, we had the summit, and we had each other. This is why we do this.