I slept for about two hours in total that night, rolling and shifting in the sleeping bag, checking my watch by the red tactical light every 20 minutes or so. I listened for a storm like the one we had the night before, but things sounded quiet outside. Will we go?

Traveler’s diarrhea had hit me several days earlier in Terskol. I’m still not certain what dining hall delicacy was responsible for my ills, but several teammates were coping with the same issue. Typically this is caused by enterotoxigenic E.coli, although a whole variety of pathogens can do the same thing, from bacteria to viruses to parasites. Usually it does not matter, because things get better on their own after 3-5 days. Symptomatic relief can be found with bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) or anti-motility drugs (Imodium), but this is optional. Antibiotics have their side effects and toxicities, which I know well. The diarrhea mantra in ID is “Let it flow.”

But, not when mountaineering. Up there, things are more complicated. You can’t just drop trou when you feel the urge to purge—the harness alone makes getting pants down challenging, and the terrain might not allow for safe defecation. Beside, focusing on my anal sphincter while climbing would be no fun. So, I decided to take meds. Bismuth is my first-line choice, but unfortunately I brought only four tabs with me on the trip, and the pharmacy in Terskol was inexplicably closed the morning we left. Teammate John kindly gave me his two tabs, so I had six for the expedition. I used them judiciously, and they helped a bit, but not enough.

Antibiotics were called for.

I always travel with azithromycin, because of its superiority to flouroquinolones for treating ETEC and Salmonella, and because it’s pretty well tolerated. This time, I made a mistake and brought just a single 500mg tab… the other tabs I thought were azithro turned out to be generic levofloxacin left over from Everest 2016 (which I brought in case my female teammates developed a UTI). So, I had less than a full course of azithro, and my buddy Steve was hurting up there too with the same thing. I gave him the tab and promised him that if things failed to improve we would try something different next. Fortunately, I did have several tabs of rifaximin left over from Everest, and started taking that. $20 per pill never tasted so good, and I sensed that things were settling down.

Now, an hour before departure on summit night, it became urgently clear that things were NOT yet under control. I scrambled to get layers on and raced out of the hut… into a spectacular night. SPEC-TAC-U-LAR. There was no wind. The air was fresh and only slightly bracing. As I negotiated my way to the lav, a shooting star streaked northward over the summit, which I could see in pure starlight. There was no moon to sully the Milky Way arching across the sky in full detail, as clear as any view I have ever had. Headlamps dotted the upper mountain, where climbers who had started earlier were making fine progress—including our own Val and Bruce with guide Alex.

I produced a full rooster tail of liquid diarrhea, nearly splattering against the far wall, but afterwards my intestines seemed to settle, and the cramping stopped. I sensed that my gut was empty, and that there would be no encores for the coming day, which was a tremendous relief.

Stepping out of the reeking lav back into the night, my pulse increased with excitement. Could this be the same mountain that had thrashed us with a blizzard 24 hours earlier? We are doing this. No more delays. I wanted to kick down the hut door and shout it out loud: “We are a go!”

But, that would have been rude. It was still 45 minutes before the wakeup call.

I was too stoked to lie down again, and instead quietly pulled my gear from the rack into the dining area and began to pack using the tactical light. Steve woke up, and I told him how perfect things were outside. We stood on the front porch and drank it in. He said, “I have not seen a night like this since the Middle East.”

“Welcome back, brother,” I clapped him on the shoulder. “Epic.”

I tried to shoot some photos of the stars, but they turned out blurry without my tripod. Tempting to set it up, but the clock was ticking and I wanted everything to be perfect with my kit.

I took meds to enhance my chances of summiting. Performance enhancing drugs… sounds like Lance Armstrong, right? I think of these as SAFETY enhancing drugs, a bit different. Aspirin to reduce my chances of a heart attack or stroke. I skipped my usual blood pressure medication, and instead swallowed a tablet of tadalafil, a phosphodiesterase blocker that can reduce the risk of HAPE during rapid ascents, although it can also drop your blood pressure. I have used it before in the Rockies and Himalayas without difficulty. Dexamethasone, just 4 mg, to protect my brain from HACE. I had more in my kit in case I developed a catastrophic headache or altered mental status… I once used this medication to help save a patient with this disorder at high camp on Aconcagua, so I know it works. And, I took more rifaximin and imodium and Pepto-Bismol. I felt like an old man taking so many pills. But I did not care. I will never come back here. It’s now or never. I MUST summit.

Mike entered the hut about 10 minutes ahead of schedule and ensured that everyone was up. He got the stoves going and began to boil water. Chaos built slowly as the dining room became the team’s staging area. By the orbs of our headlamps we ate hasty breakfasts and got our gear organized. The clatter of ice axes, swishing of parkas being stuffed into packs, blowing of noses, lacing of boots, literal stepping on each others toes… the whole cacophony proceeded with meticulous politeness. I marveled at the team: We has been total strangers just a week earlier, and now we got along beautifully.

I stepped outside briefly to check my InReach, which I was using to send and receive texts.

To Julie: “Busy getting ready, but quick version is that everything is perfect except my colon. Meds will help. Hope for summit 9 AM my time. Love you dear.”

Julie’s reply: “Wishing you a strong sphincter….”

To Kim: “Leaving in 90 minutes. Kim… it is perfect. Fucking perfect. Except my gut, all is in the bag. Here we go….”

Kim’s reply: “Boom. Piece of cake. If you gotta poop, just poop!”

Mike joined me outside. “Dude,” I said, “look at this night.”

“Yep. Looks like we may just get up this thing after all. Long time coming, P-squared.”

“Goddamn right. We’re going to nail it.”

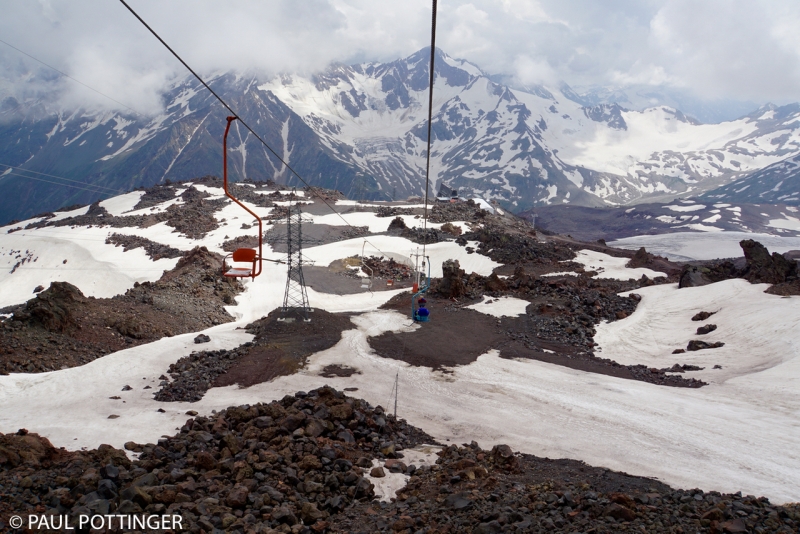

One by one we finished packing and moved outside. The Snow Cat was due at 3:00 AM sharp, and we did not want to be late. The goal was to meet Val and Bruce at the top of the Pastukhov Rocks at 3:15 AM, and we would continue as a team at that point. They had done the REAL thing and decided to climb on foot right out of the hut, which is amazing.

Now we stood outside waiting for the Snow Cat. Time and again the slope below was lit by yellow halogen headlights… and time and again they passed us by, climbing noisily up the route loaded with climbers from the Barrels. Minutes passed. I felt cold, standing still in the frozen night. I turned on the boot warmers and selected the lowest setting. No need to get cold before we even start. I danced and shook out my hands. Clearly we should have waited inside… but going back in would be a hassle now (it would mean getting the door unlocked, and everyone would have to take their spikes off). Sasha called the driver several times on her mobile phone, and the conversations were short and inscrutable. The thought of all those other parties starting out ahead of us began to weigh on me. For fuck sake, let’s go!

Our Snow Cat arrived 15 minutes late. We would not realize it until later that day, after the climb, but it had been late because some American climbers on the route had flagged the driver down for assistance when one of their teammates had collapsed and died—or so the driver believed. They hoisted his body into the back and the driver took them down to the barrels before turning around and coming up for us. To this day I do not know what really happened with the fallen climber, but based on the lack of news about this online I suspect he was ill but not dead. One American climber had died on the mountain the previous month, when caught solo in a snowstorm, and his remains had still not been found. It was awful… and the thought of another death up there was too terrible to contemplate.

The Snow Cat pulled up right in front of the hut. As we climbed into the open-air benches on the back I started my GoPro. It took a single frame, then quit. There was no time to fiddle with it. I sat in a rear corner, in hopes of shooting the whole group while we drove up. But, no dice. The camera had crashed, refusing to film, change modes, or even turn off. I had to unbolt the gimbal, remove it, and pull the battery… and when I tried to start it again, the same thing happened. I had built a customized system for this thing, and had hauled it halfway around the world and up the stupid mountain, and now the camera failed me at the last minute, just as it had above the South Summit on Everest. Really, GoPro? Someone needs to build an action camera that actually works at altitude. All the while I was squeezed by the weight of my teammates on the bench when they slid backwards as the Cat climbed steeper and steeper terrain. Several times I thought the cat might tumble over backwards, killing all of us instantly. But it seemed to have a center of gravity magically below the snow line, and of course we were fine.

As we went higher and higher, we passed climbers on their way up. The wind was frigid, and the Cat tracks kicked up a fearsome storm of icy needles that flew onto these poor souls. There was nothing they could do but stop and turn away and wait for us to roar past. I wanted to apologize to each and every one of them. Being the asshole on the mountain was unfamiliar and uncomfortable for me.

The ride stopped just beyond the rocks, at a relatively flat spot where other Cats had recently disgorged their loads of climbers who were now lining up and starting to walk uphill. We stepped down to the snow and joined the jumble. Where were Bruce, Val, and Alex? Had we missed them on the way up? I doubted it… they probably arrived here right on time and became too cold to wait for us. It was much colder here than it had been at the hut, and I needed to add both a small puffy layer and my GoreTex pants. The little OR puffy had been a gift from IMG as thanks for the images I had given them for the Everest blog this season. Of course I was happy to do it, but this was a very nice and unexpected gesture. It fit perfectly under my Ansilta softshell. I realized that this was close to the same layering system I had used on summit day on Mt. Vinson. It is friggin’ freezing up here.

Alpine starts are always painful, and this was no exception. I felt cold, especially my hands that had been in thin wool liners while I struggled with the GoPro. My breathing and heart rate were not yet at steady state. My legs were stiff as a board. It was pitch black outside. I understood Sasha’s observation that many people spin right here above the rocks, because they become so frozen, exhausted, and demoralized. I thought of the alpine start motivational poster by Semi-Rad, and smiled.

Nothing would make me spin that day, short of an emergency with a teammate. But, it still hurt.

Up we went. Getting the extra layers on and fiddling with the GoPro had put me behind, and I brought up the rear, right behind Igor. The wind was blowing respectably. I was glad to have the goggles on. The snow was crispy and crunchy, squealing in protest as my crampon points and axe spike hit it, again and again, step after step, like the sound of styrofoam being crushed underfoot.

Streams of climbers ahead of us dominated the route. I started to count the headlamps, but gave up because I needed to watch my footing. I estimated 50 climbers above, and many more below. This is going to suck.

But, Mike came through, as always. The snow was firm, and he cut across virgin slopes, straight up the mountain, putting us ahead of the others who were switching back over and over again. My experience with the French technique really paid off: the route was steep and tugged at my Achilles Tendons, but things went fine because I alternated my stance every ten steps between herringbone, left, and right positions. The sun began to rise behind these teams, backlighting them in deep reds and oranges, spindrift flashing silver at their feet in a small ground blizzard. It was spectacular. And… my GoPro failed to capture this. Again.

I sensed that Igor was having trouble finding his rhythm. He is a highly decorated and accomplished world-class mountaineer. Maybe this is just a rough start for him? When we approached the broken Snow Cat, perhaps 45 minutes after starting, he pulled to the side and gestured for me to continue. I figured he needed to take a leak. The following day I realized that during prior adventures he had sustained frostbite and nerve damage to his feet and legs, which must still hurt him up high. What price do we pay for our pursuits of high mountains?

The terrain remained steep for a time, and I sensed that the climb would be slightly tougher than I had anticipated. I focused on my breathing, putting PEEP into every breath. I focused on the rest step, and had no trouble matching Mike’s stride and pace. I focused on my systems, and found that all was well: my feet and hands were warm, my face had no frostbite, my eyes were moist behind the goggles, and my GI tract remained tolerable—a few twinges of misery, but nothing that would slow me down. My mind became empty… until the dead came back to me.

When I descended the Khumbu Icefall for the last time in May 2016, more than a year earlier, my dead patients returned to mind, one after the next, in a rapid-fire collage of pain, sorrow, and regret that I sought in vain to release.

This time there was only one patient waiting for me: Brianna.

Brianna Oas Strand was a remarkable woman. I met her about five years earlier, when she was suffering from complicated, multi-drug-resistant bacterial lung infections. Her germs were untreatable using standard antibiotics. And Bri had cystic fibrosis, which made her infections even more challenging to treat. Over the following years I got to know her and her family when I tortured her with antibiotics. I absolutely, positively tortured her. The medication regimens I prescribed were toxic, painful, expensive, and time-consuming. The drugs made her nauseated, interrupted her sleep, stained her skin, altered her bowel function, and made it unsafe for her to have children. Her kidneys, liver, bone marrow, and nervous system struggled to process these poisonous chemicals. One of the medicines needed to be infused by IV around the clock. For years she remained hooked up by a subcutaneous port to a pump stashed in a fanny pack. She named it “Chuck,” because she wanted so badly to chuck it across the room and be done with it. However, she talked about Chuck with good humor that bordered on affection.

Yes, I had tortured her. I had asked more of her than I had of any patient in my career. And she never complained. She never flinched. Not once. Where did such courage come from? She was a tiny thing, just a slender young woman, but she was the strongest person I have ever met. Again and again I asked myself what I would do in her position, and every time I came up short.

Her infection seemed to be under control for a time, and we decided to offer her a new treatment aimed at improving lung function, even though this meant stopping her antibiotics.

But, rather than making her better, removing the antibiotics allowed the infection to gain the upper hand, and she never recovered, even after we restarted them. The germs roared back and consumed her body, and the flesh literally disappeared from her frame. When she died, just a few days short of her 30th birthday, her body was a shadow of its former self. Her spirit and inner core, however, remained as strong as ever—stronger—right to the end.

The funeral overwhelmed me. In the church foyer, scores of photos of Bri throughout her lifetime, on a variety of amazing adventures. She loved life, she loved her family, and she particularly loved animals. In time, I am sure she would have become a veterinarian. In the main hall, more artifacts of her sensational life: her wedding dress, a leather saddle, Seahawks jerseys, photos of her immediate family. The church was filled with people who loved her: family, friends, and neighbors.

As we climbed higher on Elbrus I recited the eulogy I had written a month earlier. Parts of it had been too painful for me to say out loud, lest I begin to cry at the pulpit. I knew that if I broke down it would be all over for me. If I had the courage, here is what I would have said:

Thank you for involving me in this remarkable celebration of this remarkable woman’s life.

I am so fortunate to have met Bri and to have helped take care of her these past years. I am part of a multi-disciplinary team of doctors, nurses, pharmacists, microbiologists, respiratory therapists, social workers, nutritionists, and administrators, and others. All of us have been transformed by working with Brianna and her family.

To be clear, all of our patients at UW Medicine are special. Every one of them has a unique story to tell, and unique gifts to share. And we enjoy working with all of them. But, Brianna was different. She was exceptional… spectacular… unique.

In the old days, doctors used to make house calls. It’s a shame we don’t anymore, because it allowed us to see the richness of a patient’s life, to deeply understand their circumstances, to really get to know our patients. Today the patients come to us instead, and it puts us at a terrible disadvantage, sort of like capturing a beautiful animal in the rainforest and then putting it in a sterile plastic box and showing it to someone, then asking them to figure out its biology and social structure without proper context.

But, this was never an issue with Brianna. She brought her world with her wherever she went. With Bri, you always knew who she was, what she was about, her ethos, her ethics… her personality always shone through. And it was beautiful.

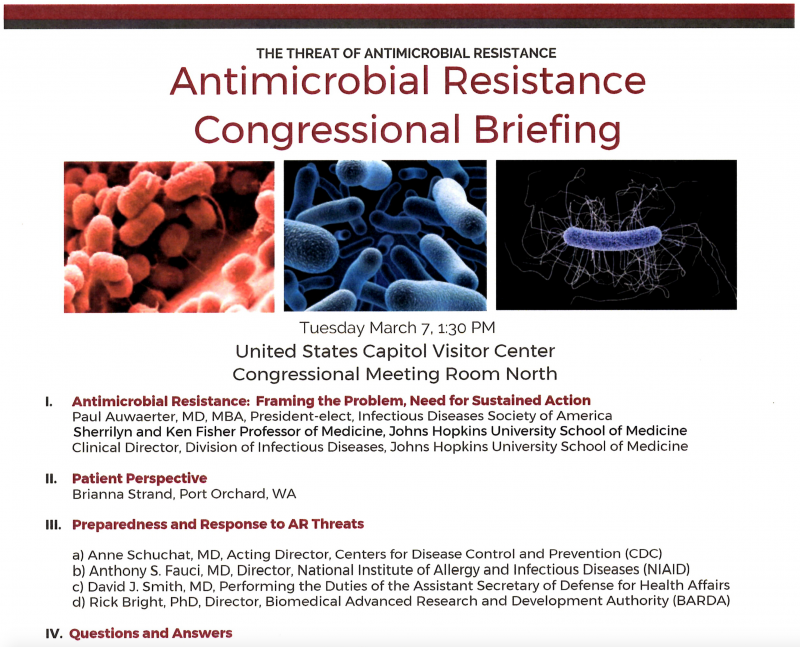

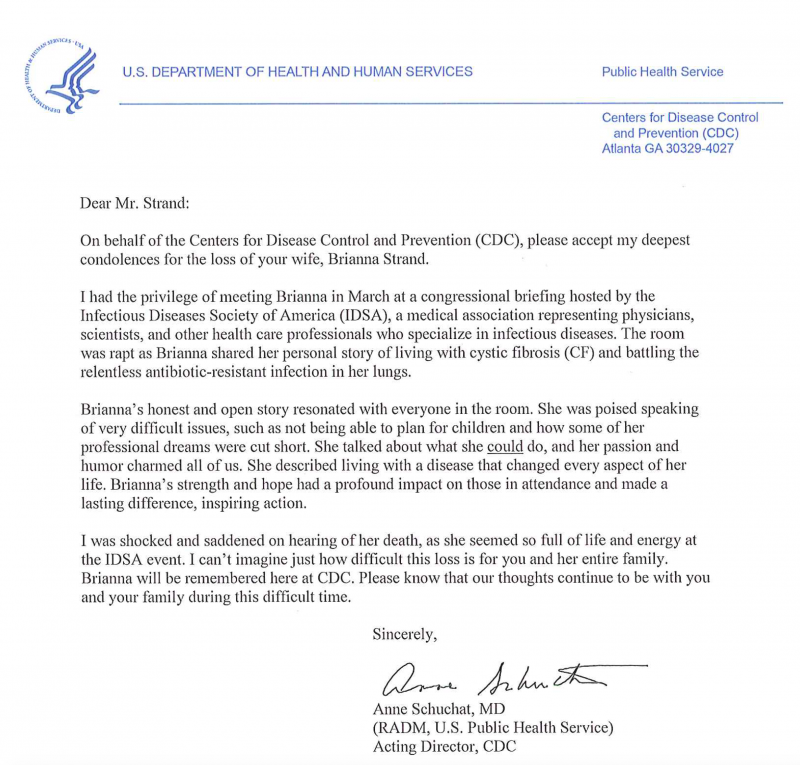

When the Infectious Diseases Society of America sent out an international call seeking extraordinary patients who could brief Congress on the crisis of antibiotic resistance, I immediately thought of Bri, and made the introduction. They were very impressed, and out of the entire world they chose her for this important mission. They flew her to Washington, DC, where she briefed our nation’s lawmakers alongside the leaders of the IDSA, CDC, NIAID, BARDA, and Johns Hopkins.

Brianna did not have to do this, but she eagerly volunteered, so that others might benefit from her experience. That was typical of Bri: It was never about her, always about others in need. She was generous, kind, and happy to help others, even though she was fighting for her own life.

I have had the privilege to work with people facing very long odds in the clinic, in the hospital, in the wilderness, in the mountains, in the most austere settings. I have met my share of brave people. But I have never met anyone as courageous as Bri. She faced unthinkable difficulties with grace, dignity, and unflinching courage. And she never, ever complained.

I was not able to be with her when she passed, which I will always regret. But we did speak by telephone. I apologized for failing her, and she forgave me. She told me there was nothing to apologize for, and she thanked me for the time I helped provide. She forgave me. I will never forget that….

In the end, her body was no match for her spirit. But her inner core remained 100% strong the whole time.

Yes, every one of our patients is special. But Brianna was different. We are trained in medical school to keep a certain distance from those we serve, not to get “too close” to them. This is for good reasons, and it usually works. But, I came to love Brianna like a niece. She was so spectacular that I could not help it. And I am grateful for our time together, for the lessons she has taught me.

A day will come when I will be meet a new patient facing similar circumstances. I will forge a strong bond with them, without feeling the pain of Brianna’s loss, without comparing them to Bri. I owe it to Brianna to stay focused on helping every patient. I promised her that I would not quit. I know a day will come when I can move forward…. But, today is not that day. I am heartbroken. Looking around this room at all of you who knew and loved her is so comforting, and so inspiring. Thank you.

https://kitsap-publishing.myshopify.com/products/brianna-strand-celebration-of-life-program

https://livestream.com/gateway/events/3739194/videos/157500260

In the weeks since she passed away I had spent time with Bri every day. This usually happened when things were quiet, or when I was driving. I would see her sitting in an empty chair, or riding beside me in the car, or standing in an open doorway. Usually she was silent, but sometimes she spoke to me in her kind, clear, confident voice. She laughed. She encouraged me to keep going, to stay focused. She praised me and thanked me for my care. She forgave me for failing her. There were times when this was simply too much for me to bear and I fought to put her out of my mind, lest I break down during a meeting, or wreck the car.

As we climbed higher on Elbrus, the sun rose over my right shoulder. I looked left and found our shadow stretching across the Caucasus, which stood in savage rows out to the horizon, razor sharp against the pale blue sky. It was spectacular. And Bri was there with me, watching it, smiling. She offered me her hand. I began to cry, as I had so many times before when thinking of her, and the tears streamed down my face and collected in the bottom of the goggles, where they froze in the foam air intakes. I shook my head in pain, but I did not shoo her away. I wanted her there. If she could fight so hard, I could certainly do this. Oh Bri, I’m so sorry. We’re going to be OK. Let’s climb this together. And we did.

Soon the route made a sharp dogleg to the left, the first traverse. Just below this turn, we stopped for a break.

I sat next to Mike. “Thank you so much for passing those turkeys back there. Perfect guiding, as always.”

“You like that? Should save us maybe 20 minutes.”

“Oh hell, more like 45,” I said. “Anyway, seriously, thank you.”

The view was amazing, and looking down on all those poor sods below soothed the ego.

A strange and lovely surprise: A photographer called Anatoliy introduced himself, and offered to take photos of the group. He was friends with Sahsa. It was odd to find paparazzi circa 16,000 feet, but we happily agreed. The shots he took turned out to be awesome.

Above the break we went a bit higher, then cut left for the traverse. It was actually a climbing traverse, but gently climbing. The upper mountain of the East Summit loomed overhead, a mix of exposed black rock and compact snow, with very little in the way of wind-loaded cornice hazard. Even so, tracks of recent snowfall and rockfall littered the slope above, and our exposure lasted longer than I would have predicted. It felt good to turn the corner and enter a deep cwm. Between the twin peaks, our next objective: the Saddle.

Elbrus has two summits, which are almost identical in height. (The West summit is slightly higher at 18,510, so it is considered the true summit, and it was our objective for the day.) Between these pyramids is a large valley, and at the bottom of the valley is the Saddle: an expanse of snow the size of several football fields.

I felt pretty good pulling into the Saddle, although I was ready for a break. We chose a spot in the sunshine and took a rest. Just above we found our friends: Bruce, Valari, and Alex were standing there, getting ready to move higher. They had been soaking up the sun for a while, and were on their feet and eager to proceed. Mike did not want them to have to wait for us to complete a proper break, and he gave Alex the go-ahead by radio to continue. We waved to them and watched them head up.

A friend gestured to my backpack. “What is that thing? Looks like a cow’s tail.” He was asking about the Tibetan Kata, a prayer scarf tied to the pack in a crude braid. Most Sherpa mountaineers carry one; everyone in the Khumbu knows what they are. For the first time it hit me, Holy cow, none of these people has climbed Everest. I thought of the day in April 2015 when I had received it in Phortse as a gift from Phunuru, head IMG climbing Sherpa. It was my 47th birthday. We were marching away from EBC several days following the earthquake that had killed 20 there, killed thousands more across the country, brought Nepal to its knees, and definitively ended our expedition. On that day, my birthday, we were fine—perfectly safe and warm in Karma Rita’s teahouse, thrilled to be alive, depressed that the season was over, and heartbroken for the dead and the dying. And we got as drunk as hell that night. Absolutely plastered. To capture the moment I asked for autographs on the scarf. Kim wrote with a sharpie, “Paulina, happy 47th, heart Kimbo Slice.” I wanted everyone to sign it, but we were too inebriated to make that happen. No matter. I kept the scarf and brought it back to Nepal for Everest 2016, braided onto my pack. It represented an indescribable mixture of joy, hope, pain, fear, regret, guilt, anxiety, and triumph. I will never untie it, even though it looks ratty on my pack.

From our break spot at the Saddle the route above was easy to see: A traverse that hugged the mountain in a steep climb. It looked exactly like the Autobahn on Denali, but running the opposite direction… smaller… and with less objective hazard. The runout on Denali ends more than a thousand feet below on the Peters Glacier; on Elbrus, the runout went right back to this gentle Saddle. Some of the more exposed sections here were protected with fixed lines, although it seemed unnecessary, especially because snow conditions were fine. The risk of a catastrophic fall here seemed small, and we were roped together for protection anyhow. Still, there’s always concern for occult crevasses, and if extra pro is available we will use it… so long as it does not slow us down.

And that was likely to be an issue today. When we pulled in for the break there was only one team of eight on the upper traverse. Bruce, Val, and Alex followed them at a good distance, and the route looked very open and inviting. But… that did not last. Several big groups got onto the route before we did, so traffic was inevitable. Mike waited a while to give them time to pull ahead, but eventually we needed to get moving.

I knew this would make the upper traverse ugly. Passing climbers headed in the same direction is always a hassle. But the creepshow on Elbrus was worse than I had anticipated.

The parade of oddities and deplorables was unlike anything I have encountered. People in single-wall fabric boots. People without a harness. People with a harness who failed to clip the line. People without crampons. People without ice axes. People with two axes… both strapped to their packs, trekking poles in hand instead. People with nothing in hand at all.

They were slow.

Very, very slow.

One person dropped her trekking pole (this may happen if you fail to use the wrist straps). It started to slide down the face; she squatted and tried to snag it with the other pole, leaning perilously out of balance away from the trail.

And then another climber wearing yellow (we dubbed him “Yellow Man”) sat down on the line and seemed to struggle, feebly, as if in a daze. The scene was very reminiscent of Everest. From the anchor position behind me, Peter shouted out in frustration. “Jesus Christ, dude, are you kidding me? Get up!” Getting to know Peter was one of the highlights of the trip. He has all the makings of a great mountaineer: good humor, strength, attention to detail, sound judgement, determination… and to this list he could now add experience dealing with incompetent teams up high.

I reassured him. “Man, you have no idea. Imagine the same scene, but 11,000 feet higher and with more exposure. It’s OK, Mike is on it. Just watch.” And, sure enough, right on cue Mike unclipped and stepped into the crusty styrofoam snow above the route. One by one we passed this knot of foolishness. When I came across Yellow Man I was horrified: He lay face down in the snow, motionless. “Dude, are you dead?” I started to probe him with the spike of my axe when he rolled over violently onto his back and cried out in agony… then lit up a cigarette. As we left him behind I thought, Stay classy, Mt. Elbrus.

At one point I looked across the cwm at the East Summit: three mountaineers climbed its spine at a serene pace, in crystalline sunlight, the entire summit pyramid to themselves. Shit, that thing is only a few feet shorter than this one… why aren’t we over there?

In the end, the upper traverse was not too bad. In fact, if it had not been loaded with eurodoofusses, it would have been fun and inspiring.

We turned left up the mountain onto a gently sloping bench and took a short break. The terrain was fine, but I felt tired. We were above 18,000 feet, and that always takes a toll on me. I thought of Nepal… on Everest, we would be in the Icefall at this elevation. Here, there was just snow underfoot. Mike announced that we were about 15 minutes below the summit. We could drop our rope here, get hydrated, put a few calories in, then get ready for strong winds above. Bruce, Val, and Alex came down, and we congratulated them… they agreed, the top was very close indeed, and it was windy. We were very happy for them.

We saddled up. I chose to finish in my balaclava and heavy parka, an unusual move for me, but it was just too damned cold to remove it after the break.

There was nothing left to do but tag the summit. At this point I walked slowly. I kept my mind clear and took in the sights. The summit area was massive, a series of gentle ridges and “football fields” covered in snow. In the distance, about 100 meters away, the true summit: A small bump of rock about the size of a house protruding into the sky. As I approached it I felt numb. The wind was ripping pretty hard but I was fine, all skin covered, as always. The gear insulated me against the cold, and in a strange way it protected me from my own emotions too. Just get there, and this will all be over.

On the final steps to the top I remembered to turn on my GoPro, the same way I had on top of Vinson. In spite of the cold, the batteries were warmed by the sunshine, and it worked.

The top was crowded with about 15 people, both strangers and teammates who had already arrived, taking summit portraits. I looked out across the landscape, in all directions. Everest was supposed to be the last of the Seven; I had been scheduled to climb this mountain in 2011, but terrorists murdered skiers and bombed the lifts that year, so the mountain was closed for the season. So here I was, six years later, standing in the sun at 9:00 AM.

The top of Europe.

Mike saw me and congratulated me. I thanked him for taking care of me for these past years, for helping me get here. He was very happy for me. All my teammates were.

The gravity of this moment hit me hard. I collapsed onto my knees and clutched the axe head that protruded from the snow. “Are you OK?” asked Mike.

I could not speak. I sobbed into the balaclava and shook my head. This is the end. We did it, Bri. We’re here. She stood there with us. I saw her as clear as day, smiling broadly. Standing beside her: my beautiful family. Julie, Zoe, and Matthew were there. And as I cried harder they knelt with me and put their arms around me. We did it together.

Here was the culmination of my ambition, my obsession these last seven years. These stupid, crazy, painful, deadly, terrible, hilarious, profane, complex, spectacular Seven Summits. I struggled to make sense of it, but I could not. I was overwhelmed.

It was profoundly cold and windy. I had to pull myself together. After a couple minutes I stood up again and posed for photos taken by Mike. In each case I held snapshots of people who had climbed the mountain with me, inside me… the people who had whispered encouragement in my ear during this seven-year odyssey.

I was sorry that Ali was not there, and that Bruce, Val, and Alex had already taken their glory shots a few minutes ahead of us. But it did not matter: We had done this the IMG way, as a team.

While my friends started down I scraped some ice and snow into my water bottle… I have gathered snow (or taken a small stone if available) from the top of each of the Seven. Now your collection is complete.

The descent was fine. The wind died down once we returned to the rope, and I could shed the parka. Once again there was traffic on the traverse, but most of it was coming up, so we passed each other quickly. I shed more layers at the Saddle. The sun was blazing, the wind was light, the snow turned to mashed potatoes, and it became a trial by UV exposure. It did not matter. I was happy. I had just climbed the Seven Summits.

During the trudge back to the hut, I was haunted by Hozier’s lyrics, which felt like an anthem for these last seven years.

I was born sick, but I love it

Command me to be well…

Amen

Take me to church

I’ll worship like a dog at the shrine of your lies

I’ll tell you my sins and you can sharpen your knife

Offer me that deathless death

Good God, let me give you my life

No masters or kings when the ritual begins

There is no sweeter innocence than our gentle sin

In the madness and soil of that sad earthly scene

Only then I am human

Only then I am clean

—Hozier

As we got lower, we realized that we could make it all the way down if we hurried and reached the top of the lifts before 3:00 PM. It looked like we might reach the hut circa 2:00 PM… meaning we would need to pack and then run down to the Barrels in an hour. Painful, and probably not feasible with such heavy loads. But the idea of sleeping in a proper bed was too attractive, and we decided to haul ass. I found new energy and purpose: We are getting off this mountain today. It reminded me of the hike off Rainier a couple weeks earlier, when we had raced against the clock to make it to Paradise Lodge before the kitchen closed. I really, really wanted a pint of Tacoma Brown Ale and a plate of “Buffaloaf” (buffalo meatloaf). And of course we made it, with three minutes to spare. And that buffalo was mighty tasty.

On Elbrus, we had an advantage: We could always order a Snow Cat. Sasha was still miffed that our ride had been 15 minutes late that morning, and she insisted that a Cat come up to the hut free of charge. We hardly paused to catch our breath when we reached the hut: hasty packing was the name of the game. Everything had to go, both personal kit and group gear. And we did it: after 30 minutes the place looked like it had been picked clean by a flock of vultures. The Cat pulled up right on schedule, to Sasha’s approval. As we loaded up, we saw a bunch of models cavorting nearby in the snow, wearing bikinis or nothing at all. It is definitely time to get out of here.

When we came off the Cat and walked to the lifts, Mike said, “Dude, now that you’ve tagged the Seven Summits, how about retiring that hat?”

I laughed. My sun protection system was undeniably goofy looking, but it worked. “Never.”

Getting back down to the valley was wonderful: warm, green, humid, comfortable. The shower was revitalizing. We ate dinner at a lovely resort: roasted meat, bread, and platters of fresh vegetables. A massive rainstorm arrived at the end of the meal. This was the most violent rainfall I have ever seen, stronger than any deluge in the tropics. Thunder boomed seconds after the blinding flashes of lighting. I loved it.

The hotel mattress awaited me. No true sleep that night, as always after the summit. I worried about the work I had missed. I thought of my family, and mourned the time I had spent away from them. But no matter. There was nothing to do about any of that for now. Behind my eyelids I watched the upper mountain, then the summit. There would be plenty of time to reflect upon our success. One thought shone through, hour after hour: You did it.

So happy for you. Thank you for sharing.

Thank you Lavinia.

Great as always, Paul!

Thanks Steve!

Congrats on bagging the 7 P2. I was in Russia just a couple of weeks before you on my first!

Love the blog. Hope you keep climbing!

Thanks Ben! Congrats… Elbrus can be a bear, so to speak. Appreciate your interest. Stay safe up there.

i like this sharing, thanks..